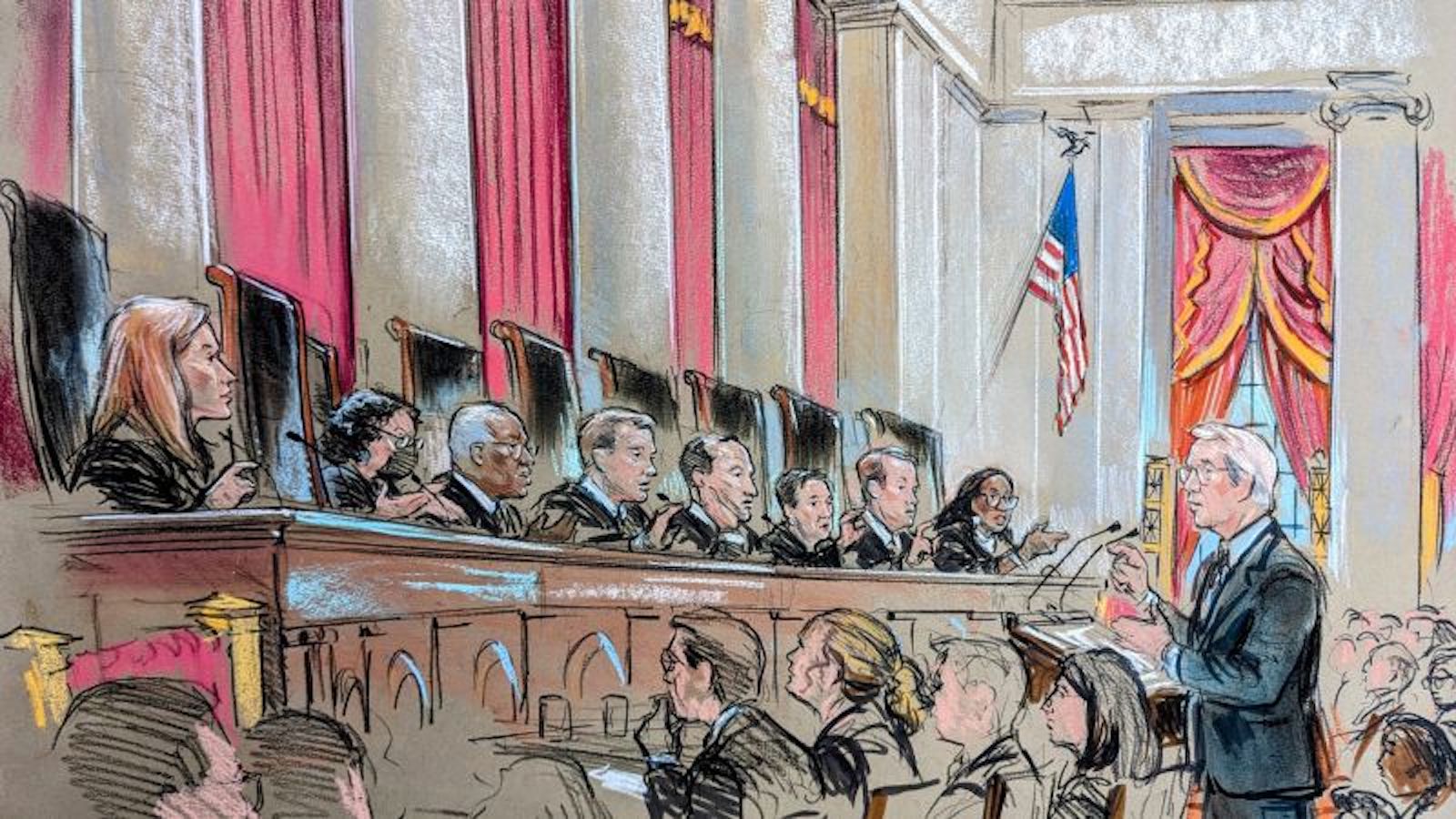

(Trends Wide) — Nine justices set out Tuesday to determine what the future of the Internet would look like if the US Supreme Court narrowed the scope of a law that some believe created the modern social media age.

After almost three hours of arguments, it was clear that the judges did not have a clear idea of what to do.

That hesitancy, coupled with the fact that the judges were entering new territory for the first time, suggests that the court in the present case is unlikely to issue a sweeping decision with unknown ramifications in one of the most recent trials. observed from this period.

Tech companies large and small have been following the case, fearful that judges could change how sites recommend and moderate content in the future and make websites vulnerable to dozens of lawsuits, threatening their very existence. .

The case before the judges was initially brought by the family of Nohemi González, an American student who was killed in a Paris bistro in 2015 after ISIS terrorists opened fire. Now, her family seeks to hold YouTube, a Google subsidiary, responsible for her death due to the site’s alleged promotion, through algorithms, of terrorist videos.

The family sued under a federal law called the 1990 Anti-Terrorism Act, which authorizes such claims for injuries “by reason of an act of international terrorism.”

Lower courts threw out the challenge, citing Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996, the law that has been used for years to provide websites immunity from what a judge on Tuesday called a “world of lawsuits.” ” that are derived from third-party content. The Gonzalez family argues that Section 230 does not protect Google from liability when it comes to targeted recommendations.

Oral arguments spiraled into a maze of issues, raising concerns about trending algorithms, miniature pop-ups, artificial intelligence, emojis, sponsorships and even Yelp restaurant reviews. But at the end of the day, the judges seemed deeply frustrated with the scope of the arguments before them and were unclear on the way forward.

One lawyer representing plaintiffs challenging the law repeatedly failed, for example, to offer substantial limiting principles to their argument that could trigger a spate of lawsuits against powerful sites like Google or Twitter or threaten the very survival of smaller sites. And some judges backed down on the mass hysteria stance put forward by a Google defender.

On several occasions, the judges have said they were confused by the arguments before them, a sign they may find a way to sidestep their opinion on the merits or send the case back to lower courts for further deliberation. At the very least, they seemed scared enough to tread carefully.

“I am afraid I am completely confused by whatever argument you are presenting at this time,” Judge Samuel Alito said from the outset. “I guess I’m completely confused,” Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson said at another point. “I’m still confused,” Justice Clarence Thomas said mid-argument.

Justice Elena Kagan even suggested that Congress intervene. “I mean, we are a court. We really don’t know about these things. You know, these are not like the top nine Internet experts,” she said with a laugh.

But in court, Eric Schnapper, a lawyer for the family, repeatedly made much broader arguments that could affect other areas of third-party content.

Yet even Thomas, who has expressed reservations about the scope of Section 230 before, seemed skeptical. He sought clarification from Schnapper on how one could distinguish between algorithms that “present cooking videos to people interested in cooking and ISIS videos to people interested in ISIS.”

Alito asked if Google might have just been organizing the information, rather than recommending any type of content.

“I don’t know where he’s drawing the line,” Alito said.

Chief Justice John Roberts tried to make an analogy with a book seller. He suggested that Google recommending certain information is no different than a book seller sending a reader to a table of books with related content.

At one point, Kagan suggested that Schnapper was trying to gut the entire statute: “Does your position send us down the road such that 230 can’t mean anything at all?” he asked.

When Lisa Blatt, a lawyer for Google, stood up, she warned the judges that Section 230 “created the internet today” because “Congress made that decision to prevent lawsuits from stifling the internet in its infancy.”

“Exposing websites to liability for implicitly recommending the context of a third party defies the text [230] and threatens today’s Internet,” he added.

In the end, Schnapper appeared to speak for the court when he said that “it’s hard to do this in the abstract.”

(Trends Wide) — Nine justices set out Tuesday to determine what the future of the Internet would look like if the US Supreme Court narrowed the scope of a law that some believe created the modern social media age.

After almost three hours of arguments, it was clear that the judges did not have a clear idea of what to do.

That hesitancy, coupled with the fact that the judges were entering new territory for the first time, suggests that the court in the present case is unlikely to issue a sweeping decision with unknown ramifications in one of the most recent trials. observed from this period.

Tech companies large and small have been following the case, fearful that judges could change how sites recommend and moderate content in the future and make websites vulnerable to dozens of lawsuits, threatening their very existence. .

The case before the judges was initially brought by the family of Nohemi González, an American student who was killed in a Paris bistro in 2015 after ISIS terrorists opened fire. Now, her family seeks to hold YouTube, a Google subsidiary, responsible for her death due to the site’s alleged promotion, through algorithms, of terrorist videos.

The family sued under a federal law called the 1990 Anti-Terrorism Act, which authorizes such claims for injuries “by reason of an act of international terrorism.”

Lower courts threw out the challenge, citing Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996, the law that has been used for years to provide websites immunity from what a judge on Tuesday called a “world of lawsuits.” ” that are derived from third-party content. The Gonzalez family argues that Section 230 does not protect Google from liability when it comes to targeted recommendations.

Oral arguments spiraled into a maze of issues, raising concerns about trending algorithms, miniature pop-ups, artificial intelligence, emojis, sponsorships and even Yelp restaurant reviews. But at the end of the day, the judges seemed deeply frustrated with the scope of the arguments before them and were unclear on the way forward.

One lawyer representing plaintiffs challenging the law repeatedly failed, for example, to offer substantial limiting principles to their argument that could trigger a spate of lawsuits against powerful sites like Google or Twitter or threaten the very survival of smaller sites. And some judges backed down on the mass hysteria stance put forward by a Google defender.

On several occasions, the judges have said they were confused by the arguments before them, a sign they may find a way to sidestep their opinion on the merits or send the case back to lower courts for further deliberation. At the very least, they seemed scared enough to tread carefully.

“I am afraid I am completely confused by whatever argument you are presenting at this time,” Judge Samuel Alito said from the outset. “I guess I’m completely confused,” Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson said at another point. “I’m still confused,” Justice Clarence Thomas said mid-argument.

Justice Elena Kagan even suggested that Congress intervene. “I mean, we are a court. We really don’t know about these things. You know, these are not like the top nine Internet experts,” she said with a laugh.

But in court, Eric Schnapper, a lawyer for the family, repeatedly made much broader arguments that could affect other areas of third-party content.

Yet even Thomas, who has expressed reservations about the scope of Section 230 before, seemed skeptical. He sought clarification from Schnapper on how one could distinguish between algorithms that “present cooking videos to people interested in cooking and ISIS videos to people interested in ISIS.”

Alito asked if Google might have just been organizing the information, rather than recommending any type of content.

“I don’t know where he’s drawing the line,” Alito said.

Chief Justice John Roberts tried to make an analogy with a book seller. He suggested that Google recommending certain information is no different than a book seller sending a reader to a table of books with related content.

At one point, Kagan suggested that Schnapper was trying to gut the entire statute: “Does your position send us down the road such that 230 can’t mean anything at all?” he asked.

When Lisa Blatt, a lawyer for Google, stood up, she warned the judges that Section 230 “created the internet today” because “Congress made that decision to prevent lawsuits from stifling the internet in its infancy.”

“Exposing websites to liability for implicitly recommending the context of a third party defies the text [230] and threatens today’s Internet,” he added.

In the end, Schnapper appeared to speak for the court when he said that “it’s hard to do this in the abstract.”