(Trends Wide) — Abortion today, at least in the United States, is a political, legal, and moral tinderbox. But for long stretches of history, terminating an unwanted pregnancy, especially in the early stages, was an uncontroversial fact of life, historians say.

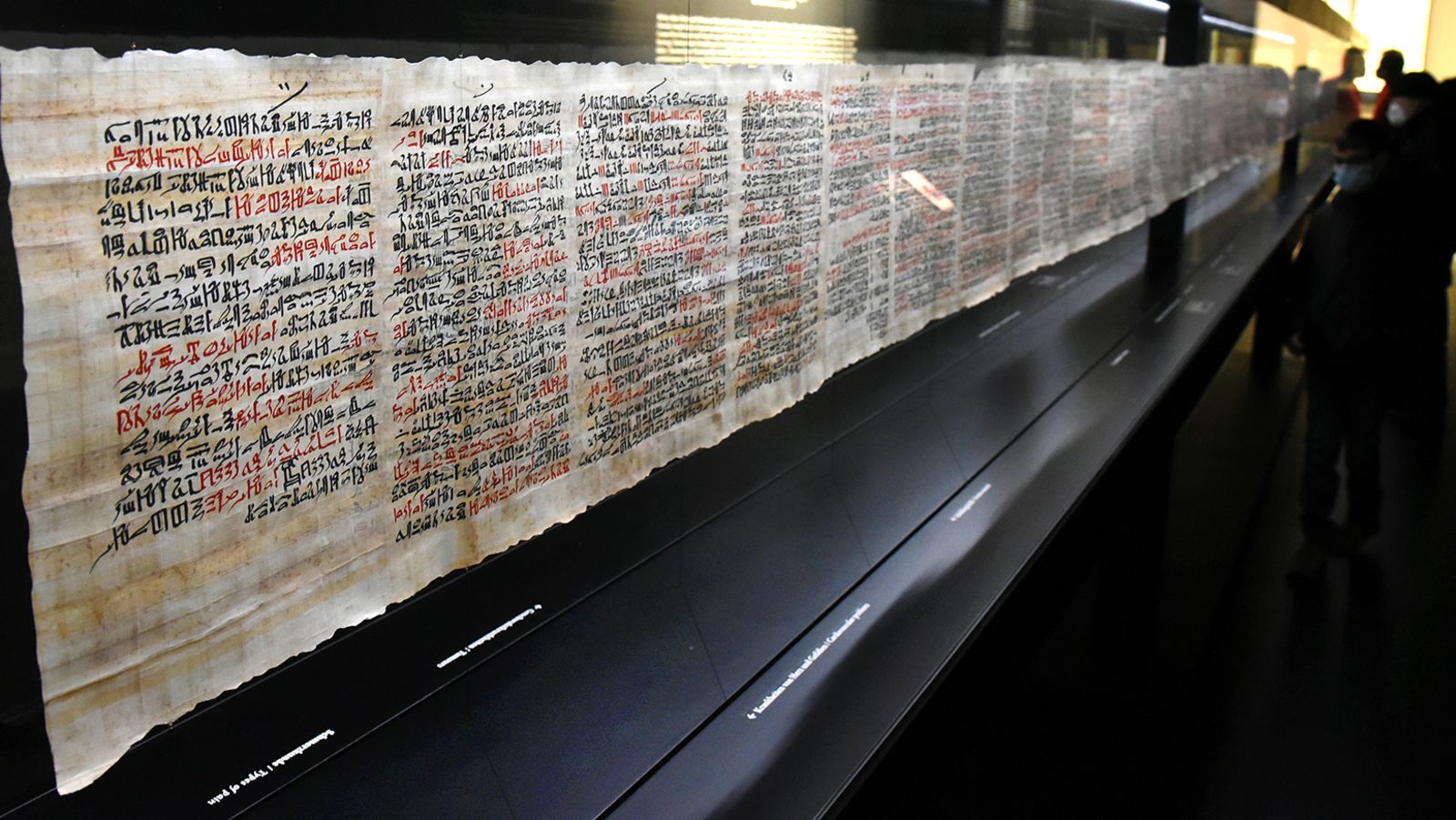

Egyptian papyri, Greek plays, Roman coins, medieval biographies of saints, medical and obstetric manuals, and Victorian newspapers and pamphlets reveal that abortion was more common in pre-modern times than people might think.

This historical view of abortion is important, according to Mary Fissell, a professor of the history of medicine at Johns Hopkins University. That’s because assumptions about what abortion looked like in the past color current arguments about abortion rights. Those rights have been severely restricted in many US states since the Roe v. Wade Act of 1973 that effectively made abortion legal was struck down on June 24, 2022 by the US Supreme Court in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization.

Opponents of abortion portray the rights granted by Roe v. Wade and legal access to abortion as a historical aberration, according to Fissell, which is not accurate, historians say.

“We have to understand that this is much more changing than we have been led to believe. There has been a pattern of women terminating their pregnancies throughout history, but the meanings of that act have changed very significantly over time and will continue to change,” said Fissell, who is working on “Long Before Roe,” a book about the history of abortion to be published in 2025.

“Dobbs’s decision was not inevitable, but part of a much longer cycle of restriction versus acceptance,” he said.

First references to abortion

The first written references to abortion are contained in an ancient Egyptian papyrus written some 3,500 years ago. The Ebers Papyrus, a medical text, suggested around 1,550 B.C. C. that abortion could be induced using a “vegetable fiber tampon coated with a compound that included honey and crushed dates.”

In ancient Greece and Rome, references to abortion and abortion-inducing botanicals were common in medical and other texts, though it’s unclear how widely they were used, Fissell said.

The Greek heroine Lysistrata (History/Shutterstock)

In 411 B.C. BCE, the Greek dramatist Aristophanes in his play Lysistrata described a desirable young woman as “trimmed and adorned with pennyroyal,” a plant believed to induce abortion.

Plants and botanical substances can have toxic effects, and there is no evidence whether or not historical methods of inducing abortion were effective.

the search for silphium

In ancient Rome, another plant thought to terminate an unwanted pregnancy (among other uses) was valued so highly that it disappeared — the first recorded extinction in world history, according to archaeologist Lisa Briggs, a Cranfield University researcher and researcher. Visitor at the British Museum.

Silphium or silphium, also used to flavor food, was traded throughout the ancient Roman Empire. The city state of Cyrene (in present-day Libya), the only region where the plant grew, based its entire economy on the plant. It turned up on coins and other artifacts unearthed in the region, Briggs said.

“Contemporary authors said that it was worth its weight in gold and silver. And so it clearly had a value beyond its taste. I suspect women’s desire to use it as an abortifacient is one reason the price went up,” said Briggs, who is looking for archaeological evidence of the plant, which turned into resin, in shipwrecks and museum collections.

Pliny the Elder, a Roman author and philosopher who was born around AD 23, described the plant’s ability to expel a fetus along with other medical uses. It’s impossible to know for sure whether the plant would have had the desired effect, but modern studies on related splint plants and laboratory rats showed that the plants “exhibit anti-fertility properties in rodents,” Briggs wrote in an article last year in the one who is a co-author.

Briggs believes that the demand for the plant among women may have been a key factor, though not the only reason, for its extinction. The plant was hardy to be cultivated, Briggs noted, and climate change and a change in soil characteristics may also have been factors.

A coin depicting the now-extinct silphium plant dates to 480-435 BC. (Heritage Images/Getty Images)

abortionists who were saints

It is sometimes assumed that Christianity has always unequivocally condemned abortion, but Maeve Callan, a professor and historian of religion at Simpson College in Iowa, said this misrepresents the past.

“People act as if there is only an acceptable attitude towards abortion if you are a Catholic, or if you are a Christian in general, or even if you are religious in general. And there has always been a diversity of viewpoints,” said Callan, author of the book “Sacred Sisters: Gender, Sanctity, and Power in Medieval Ireland.”

His research, along with that of other scholars, has uncovered four medieval Irish saints who celebrated the termination of pregnancy among their miracles, according to medieval manuscripts describing the lives of the saints. Typically, these miracles included a nun who violates her vow of chastity and becomes pregnant but for whom—through the saint’s intervention—the pregnancy miraculously disappears.

The most famous was Saint Brigid, a lesser-known patron saint of Ireland than Patrick, and whose position was honored with a public holiday this year.

According to an ecclesiastic named Cogitosus, who wrote Brigid’s first biography around AD 650, some 200 years after her birth, she miraculously terminated a woman’s unwanted pregnancy, “causing the fetus to disappear unborn and without pain”.

Dancers perform in front of an image of Saint Bridget projected at The Wonderful Barn in Leixlip, Kildare, Ireland, on January 31. (Peter Morrison/AP)

Another saint, Ciarán de Saigir, rescued a nun kidnapped by a king, according to a biography: “When the man of God returned to the monastery with the girl, she confessed that she was pregnant. Then the man of God, carried away by the zeal for justice, not wanting the seed of the serpent to live, pressed the womb of her with the sign of the cross and forced her to empty it.

Callan is quick to point out that these Irish saints were not advocates of women’s freedom of choice when it came to unwanted pregnancies, nor were these saints likely to perform abortions.

“Miracles show people’s attitudes toward abortion. In some circumstances it was considered acceptable, or even a miraculous blessing.”

According to Callan, in “The Old Irish Penitential”, a book that details the punishments for sins, the penance for abortion depended on the stage of pregnancy, divided into three, like trimesters: in the first, three and a half years of penance; in the second, seven years; in the third, 14 years. But as Callan said, “pretty much everything was sin.” The Old Irish Penitential also stipulates that oral sex deserves four or five years’ penance the first time, seven years if it is repeated.

“It is not permissive. Abortion is not okay (according to these teachings). It’s a minor sin.”

The idea that life begins at conception became dominant in Catholic teachings only about 150 years ago, according to Callan.

Previously, Catholic teachings suggested that a fetus becomes a person a few weeks, if not months, later, once it receives a rational soul. This is often associated with “racing”, when the mother feels the fetus move for the first time, usually in the fifth month of pregnancy.

It was not until 1588 that Pope Sixtus V officially classified abortion, regardless of the stage of fetal development, as homicide. However, after Sixtus’ death in 1590, Pope Gregory XIV quickly rolled back the dictation, limiting it to fetuses with a soul.

Why is the long-term vision important?

In research for her next book, Fissell said she had found that “what people don’t like about abortion changes significantly over time.”

In ancient Rome, for example, abortion was only a problem for elite women, who were thought to cover up adulterous relationships. In the Renaissance, abortion was linked to witchcraft. For most of history, abortion has not been an issue related to the fetus, as it is today, but rather to the behavior of women.

“All this innocent unborn life that is in the language of the American right today exists only (in the last) decades. Sometimes people didn’t like abortion because it involved illicit sex. Women have always terminated pregnancies, as far as we can see from the historical records,” Fissell said. “I think the long-term view is really important. Things weren’t always the way they are today.”

(Trends Wide) — Abortion today, at least in the United States, is a political, legal, and moral tinderbox. But for long stretches of history, terminating an unwanted pregnancy, especially in the early stages, was an uncontroversial fact of life, historians say.

Egyptian papyri, Greek plays, Roman coins, medieval biographies of saints, medical and obstetric manuals, and Victorian newspapers and pamphlets reveal that abortion was more common in pre-modern times than people might think.

This historical view of abortion is important, according to Mary Fissell, a professor of the history of medicine at Johns Hopkins University. That’s because assumptions about what abortion looked like in the past color current arguments about abortion rights. Those rights have been severely restricted in many US states since the Roe v. Wade Act of 1973 that effectively made abortion legal was struck down on June 24, 2022 by the US Supreme Court in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization.

Opponents of abortion portray the rights granted by Roe v. Wade and legal access to abortion as a historical aberration, according to Fissell, which is not accurate, historians say.

“We have to understand that this is much more changing than we have been led to believe. There has been a pattern of women terminating their pregnancies throughout history, but the meanings of that act have changed very significantly over time and will continue to change,” said Fissell, who is working on “Long Before Roe,” a book about the history of abortion to be published in 2025.

“Dobbs’s decision was not inevitable, but part of a much longer cycle of restriction versus acceptance,” he said.

First references to abortion

The first written references to abortion are contained in an ancient Egyptian papyrus written some 3,500 years ago. The Ebers Papyrus, a medical text, suggested around 1,550 B.C. C. that abortion could be induced using a “vegetable fiber tampon coated with a compound that included honey and crushed dates.”

In ancient Greece and Rome, references to abortion and abortion-inducing botanicals were common in medical and other texts, though it’s unclear how widely they were used, Fissell said.

The Greek heroine Lysistrata (History/Shutterstock)

In 411 B.C. BCE, the Greek dramatist Aristophanes in his play Lysistrata described a desirable young woman as “trimmed and adorned with pennyroyal,” a plant believed to induce abortion.

Plants and botanical substances can have toxic effects, and there is no evidence whether or not historical methods of inducing abortion were effective.

the search for silphium

In ancient Rome, another plant thought to terminate an unwanted pregnancy (among other uses) was valued so highly that it disappeared — the first recorded extinction in world history, according to archaeologist Lisa Briggs, a Cranfield University researcher and researcher. Visitor at the British Museum.

Silphium or silphium, also used to flavor food, was traded throughout the ancient Roman Empire. The city state of Cyrene (in present-day Libya), the only region where the plant grew, based its entire economy on the plant. It turned up on coins and other artifacts unearthed in the region, Briggs said.

“Contemporary authors said that it was worth its weight in gold and silver. And so it clearly had a value beyond its taste. I suspect women’s desire to use it as an abortifacient is one reason the price went up,” said Briggs, who is looking for archaeological evidence of the plant, which turned into resin, in shipwrecks and museum collections.

Pliny the Elder, a Roman author and philosopher who was born around AD 23, described the plant’s ability to expel a fetus along with other medical uses. It’s impossible to know for sure whether the plant would have had the desired effect, but modern studies on related splint plants and laboratory rats showed that the plants “exhibit anti-fertility properties in rodents,” Briggs wrote in an article last year in the one who is a co-author.

Briggs believes that the demand for the plant among women may have been a key factor, though not the only reason, for its extinction. The plant was hardy to be cultivated, Briggs noted, and climate change and a change in soil characteristics may also have been factors.

A coin depicting the now-extinct silphium plant dates to 480-435 BC. (Heritage Images/Getty Images)

abortionists who were saints

It is sometimes assumed that Christianity has always unequivocally condemned abortion, but Maeve Callan, a professor and historian of religion at Simpson College in Iowa, said this misrepresents the past.

“People act as if there is only an acceptable attitude towards abortion if you are a Catholic, or if you are a Christian in general, or even if you are religious in general. And there has always been a diversity of viewpoints,” said Callan, author of the book “Sacred Sisters: Gender, Sanctity, and Power in Medieval Ireland.”

His research, along with that of other scholars, has uncovered four medieval Irish saints who celebrated the termination of pregnancy among their miracles, according to medieval manuscripts describing the lives of the saints. Typically, these miracles included a nun who violates her vow of chastity and becomes pregnant but for whom—through the saint’s intervention—the pregnancy miraculously disappears.

The most famous was Saint Brigid, a lesser-known patron saint of Ireland than Patrick, and whose position was honored with a public holiday this year.

According to an ecclesiastic named Cogitosus, who wrote Brigid’s first biography around AD 650, some 200 years after her birth, she miraculously terminated a woman’s unwanted pregnancy, “causing the fetus to disappear unborn and without pain”.

Dancers perform in front of an image of Saint Bridget projected at The Wonderful Barn in Leixlip, Kildare, Ireland, on January 31. (Peter Morrison/AP)

Another saint, Ciarán de Saigir, rescued a nun kidnapped by a king, according to a biography: “When the man of God returned to the monastery with the girl, she confessed that she was pregnant. Then the man of God, carried away by the zeal for justice, not wanting the seed of the serpent to live, pressed the womb of her with the sign of the cross and forced her to empty it.

Callan is quick to point out that these Irish saints were not advocates of women’s freedom of choice when it came to unwanted pregnancies, nor were these saints likely to perform abortions.

“Miracles show people’s attitudes toward abortion. In some circumstances it was considered acceptable, or even a miraculous blessing.”

According to Callan, in “The Old Irish Penitential”, a book that details the punishments for sins, the penance for abortion depended on the stage of pregnancy, divided into three, like trimesters: in the first, three and a half years of penance; in the second, seven years; in the third, 14 years. But as Callan said, “pretty much everything was sin.” The Old Irish Penitential also stipulates that oral sex deserves four or five years’ penance the first time, seven years if it is repeated.

“It is not permissive. Abortion is not okay (according to these teachings). It’s a minor sin.”

The idea that life begins at conception became dominant in Catholic teachings only about 150 years ago, according to Callan.

Previously, Catholic teachings suggested that a fetus becomes a person a few weeks, if not months, later, once it receives a rational soul. This is often associated with “racing”, when the mother feels the fetus move for the first time, usually in the fifth month of pregnancy.

It was not until 1588 that Pope Sixtus V officially classified abortion, regardless of the stage of fetal development, as homicide. However, after Sixtus’ death in 1590, Pope Gregory XIV quickly rolled back the dictation, limiting it to fetuses with a soul.

Why is the long-term vision important?

In research for her next book, Fissell said she had found that “what people don’t like about abortion changes significantly over time.”

In ancient Rome, for example, abortion was only a problem for elite women, who were thought to cover up adulterous relationships. In the Renaissance, abortion was linked to witchcraft. For most of history, abortion has not been an issue related to the fetus, as it is today, but rather to the behavior of women.

“All this innocent unborn life that is in the language of the American right today exists only (in the last) decades. Sometimes people didn’t like abortion because it involved illicit sex. Women have always terminated pregnancies, as far as we can see from the historical records,” Fissell said. “I think the long-term view is really important. Things weren’t always the way they are today.”