On Wednesday of last week, shortly before 7 a.m. on West 54th Street in Manhattan, two blocks away from my old Jesuit community, Brian Thompson, the chief executive officer of UnitedHealthcare, was murdered. Even for jaded New Yorkers, the shooting was shocking. That it took place in one of the busiest parts of Manhattan, on the day of the lighting of the Christmas tree at Rockefeller Center, when the area was filled with uniformed police officers, was stunning. Equally surprising was that the suspect—tentatively identified as Luigi Mangione—eluded authorities for several days.

Perhaps even more surprising was the response in some places to this crime: celebration, lionization and valorization of the killer. Almost immediately after Mr. Thompson’s death, the shooter was praised as a hero, a modern-day Robin Hood, although, unlike the famous bandit of English folklore, he had given nothing to the poor. No matter: The killing was seen as a blow to the evils of—take your pick—the healthcare industry, insurance companies, capitalism or society overall. According to The New York Times, sweatshirts resembling the ones that the suspect wore were “flying off the shelves” and a group gathered in Washington Square Park to stage a lookalike contest. Comments online focused on people’s visceral hatred for both the insurance and health care industries.

As someone with a mother in a nursing home, and whose sister has taken on the burdens of navigating the complicated insurance industry for her; as a spiritual director who regularly hears about the medical challenges of directees; and as an aging person with other aging friends, I understand that there is tremendous anger against the insurance industry. Still, it was an ugly shock to read comments praising the shooting. A quick glance at Instagram and TikTok reveals posts—I’m sure you’ve seen them—by people offering to pay for the shooter’s legal bills and crowing over Mr. Thompson’s death.

I will leave it up to social scientists and psychologists to provide definitive answers to why our culture has become so hardened. But let me offer a few thoughts on the matter.

First of all, people are angry and resentful over many things: mainly, the economy and the lack of meaningful jobs with decent wages, as well as the perceived but false “stealing” of jobs by migrants. If you’re on the right, you may be angry about “wokeness,” and if you’re on the left, you may be angry about the overturning of Roe v. Wade. In their anger and resentment, some people feel justified in acting out, as we saw at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021. In his last column for The New York Times, Paul Krugman pointed out that even billionaires are, bizarrely, also resentful. At some point, however, one has to ask if everyone gets a free pass if they are angry or resentful to do whatever they feel like.

Second, it has become more acceptable to hate and demonize people—and to do so publicly. It’s O.K. to be, in a word, mean. The last presidential election saw migrants, refugees and transgender people treated as barely human. In previous decades, political figures would hang their heads in shame if it was revealed that they had spoken disparagingly about a particular group of people; now their mocking comments are emblazoned on T-shirts. And, as historians often point out, when you use dehumanizing language against a particular group (e.g., “animals,” “vermin,” “monsters”) it becomes far easier to see people as not deserving of our respect or care and as even deserving death. This was the tactic used by Germans against Jews, Tutsi against Hutu in Rwanda and, in our own country, government officials against enslaved people and Native Americans.

A third reason for the increased hatred is that social media can make us less connected to reality. Social media can help people feel connected, learn about the world and even pray. But if you stay logged on long enough, you’ll also see videos of people being humiliated, mocked and dehumanized for sport. “LOL.” Everything becomes a game, a joke, a meme. In the process, everything becomes less real, as Neil Postman wrote in his prescient 1985 book on the media, Amusing Ourselves to Death. In past decades, readers of newspapers followed with fascination the pursuits of people like Billy the Kid, Bonnie and Clyde, John Dillinger or, more recently, the “subway shooter” Bernhard Goetz. But social media makes murder even more of a game, distancing ourselves further from the reality of people’s suffering.

Let me add a final reason: human nature. Cruelty is as old as humankind. And murdering because of resentment is a staple of the Bible. The first murder in the Old Testament—Cain murdering Abel—occurred because Cain was furious that his brother’s offerings were more pleasing to God. King David wanted his general Uriah’s beautiful wife, Bathsheba, so he arranged to have Uriah killed in battle. Earlier, Saul tried to have David killed three times out of resentment over the latter’s popularity and military successes. In the New Testament, Judas betrayed Jesus for a few pieces of silver, for reasons still debated, but most likely because he felt Jesus was not the kind of Messiah he wanted. Each man felt justified in his reasons, but in each case their selfish reasoning led to death, as well as guilt and, in the case of Judas, suicide.

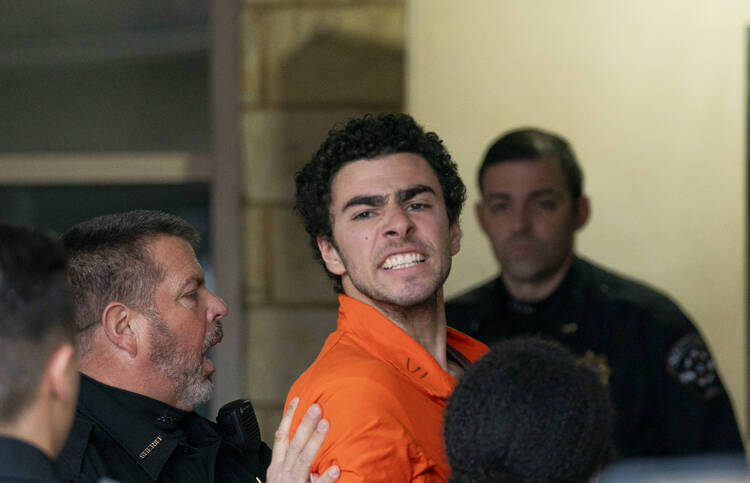

How do we live in a world of enraging injustices and clear unfairness? A well-educated person like Mr. Mangione, a prep school and Ivy League grad, could have worked for change, which takes time. Instead, the suspected shooter opted for murder. Who knows his reasons and motivations? It seems Mr. Mangione was suffering from physical pain and, most likely, mental and emotional problems. But whatever his reasons, in doing what he allegedly did on West 54th Street, he squandered his own life, took the life of Mr. Thompson and made miserable the lives of Mr. Thompson’s family. For someone who wanted to take revenge on pain—his own or that of others—he only increased it. We should lament his actions, not celebrate them.