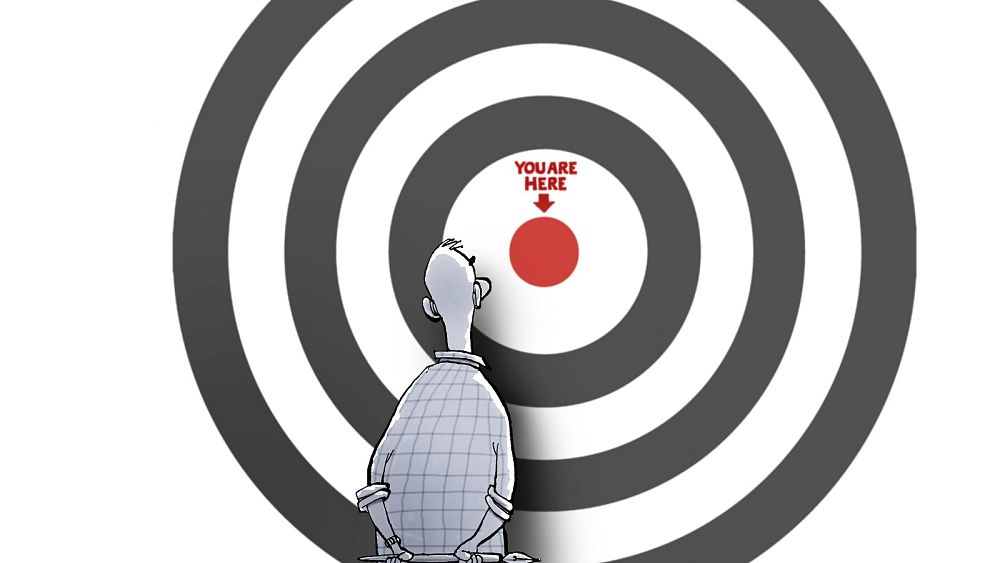

An international contest of satirical cartoons, open to 160 artists from 44 different countries, is attempting to remind us of both the beauty of the art and the danger those who create it are facing.

The related exhibition, set up in Conversano, near Bari in Italy, will display the best works chosen by a jury of experts.

“The COVID-19 crisis, with exceptional laws approved or decided without consulting parliaments in some countries, has worsened the situation as regards freedom of the press, freedom of expression and political satire, with an almost general indifference on the part of public opinion,” the organiser of the initiative, Thierry Vissol, Director of the Librexpression Centre-Giuseppe Di Vagno Foundation, told Euronews.

“For this reason, we have chosen this theme, the foundation of every democratic life”.

In January 2020, at the beginning of the pandemic, Niels Bo Bojesen, a Danish cartoonist, was targeted by the Chinese government for having published a cartoon in the Jyllands Posten newspaper in which the stars of the Chinese flag were being replaced by the new coronavirus. He and the newspaper faced demands for a formal apology from the Chinese embassy in Denmark.

Since the end of April 2020, the cartoonist Gàbor Pàpai and his newspaper have been under threat of denunciation by Viktor Orbán’s ruling party, Fidesz, for the publication of a cartoon depicting Jesus Christ on the cross, which was considered blasphemous.

In a letter published in June, the European Federation of Journalists listed further such examples.

In December 2019, cartoons by Palestinian Mohammad Saba’aneh which were being exhibited at the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague disappeared without explanation for a few hours, only to reappear under police escort.

Some cartoonists, such as Russian satirist Denis Lopatin, were forced into exile to avoid jail. Lopatin had published a cartoon showing the chief prosecutor of Crimea dressed as a nun cradling a phallic-shaped representation of Nicholas II, the last emperor of Russia and saint of the Russian Orthodox Church.

In Sweden, a Palestinian-born cartoonist, Mahmoud Abbas, was the subject of threats following the publication of a cartoon about the collapse of oil prices in April due to the pandemic. The cartoon went viral in Saudi Arabia because the protagonist in the cartoon was approached by Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman. Abbas has been called a “terrorist” and personal information about his family and whereabouts has been circulated online.

In April 2019, after publishing a cartoon criticising President Trump’s policy in Israel, the New York Times newspaper made the decision to stop publishing satirical cartoons at all so as “not offend some of its readers.” It was described as “preventive self-censorship” by Patrick Chappatte, one of the two cartoonists shown the door.

He is not alone. In the US, there were more than 2,000 editorial cartoonists a century ago; today there are just 25 left.

In Italy, apart from the Tuscan Vernacoliere, satirical newspapers and magazines have practically disappeared. Attempts to revive them, like Pino Zac’s “Il Male” from the 1970s, have not been successful.

Some web-based satirical magazines exist, but not able to successful enough to remunerate the cartoonists who produce artwork for them. France is the exception to the rule, boasting a stable of such publications, including Le Canard Enchaîné, Charlie Hebdo, Siné Mensuel and Siné Madame, or newspapers such as “Courrier International.”

“Very often we forget that editorial cartoonists are journalists in their own right,” concludes Vissol.

“Satire is a whiplash that should help to open debate […] asks questions for which citizens have the right to receive true answers and not anesthetised.”

The exhibition ‘Down with satire’ is organised by the Librexpression Centre-Giuseppe Di Vagno Foundation at Conversano castle in Bari, Italy, from September 25 to December 6 2020.

The works of the 55 semifinalists and finalists of the international contest will be exhibited. These are just some of them.