(Trends Wide) — Chilling details of the chaotic and bloody aftermath of the Uvalde school massacre show how emergency medics desperately treated multiple victims wherever they could and with whatever equipment they had, according to never-before-heard interviews.

Some doctors came from off-duty or far away to support their colleagues sent to Robb Elementary School, where classrooms had become death zones but lives still remained to be saved.

There was the state trooper with emergency medical certification who always carried five chest seals with him, never imagining that he would need them all at once; the local EMT who crouched behind a wall when shots rang out and was soon tending to three children at once; and his off-duty colleague who was found babysitting his son’s classmates, not knowing if his own son was alive.

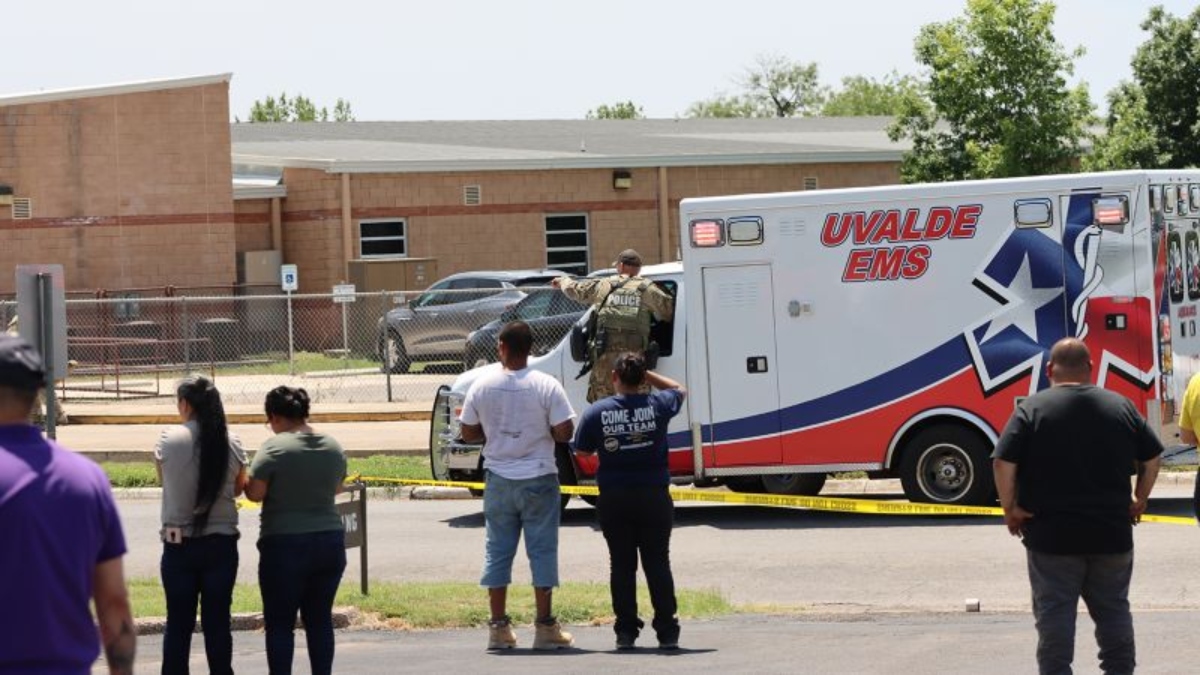

Amanda Shoemake was in the first Uvalde EMS ambulance to arrive at the school on May 24, she told a DPS investigator. in English) from Texas. But with law enforcement officers waiting for 77 minutes to challenge the shooter, she spent time trying to direct traffic to maintain a lane for ambulances to pass once victims began to emerge, she said, according to police records. investigation obtained by Trends Wide.

“We were waiting for what seemed like a while. And then someone … came and said, ‘Okay, we need EMS now,'” he said in the interview, part of the DPS investigation into the failed response to the school shooting, which killed 19 children and two teachers. At least one teacher and two children were alive when officers finally broke into the classrooms, but they later died.

When Shoemake and her colleagues arrived at the school building, they were told the attacker had not yet been found and that he might be on the roof, she said, saying they took cover behind a brick wall as they confronted the attacker.

“We just crouched there and waited until the shooting stopped,” he said. “And then after a while, they brought out the first child who was an obvious DOA.”

DPS Trooper Zach Springer was one of hundreds of law enforcement officers from across Southwest Texas who responded to Robb when alerts for reinforcements were issued. He had been certified as an EMT a few months earlier, he told the Texas Ranger that he interviewed him.

Hundreds of armed police officers flocked to Uvalde on the day of the shooting. (Credit: Jordan Vonderhaar/Getty Images)

“I made a conscious decision not to bring my rifle,” he said as he drove. “I knew there were so many people up there that they weren’t going to need rifles, they were going to need medical equipment.”

Springer entered the school and began preparing a staging area down the hall where armed officers from the school force, the local police department, sheriff’s office, state police and federal agencies were lined up. While commanders such as then-school police chief Pete Arredondo, then-acting city police chief Mariano Pargas and Sheriff Rubén Nolasco gave various statements about whether they knew the children were injured and in need of rescue, medics from many agencies were prepared for the victims.

“I prepared myself the best I could,” he said. “I put tourniquets, gauze, Israeli bandages, compression bandages, hemostatic gauze. I was like, ‘I think I have everything’… He had five stamps on his chest, which is ridiculous in my opinion, like I was making a fool of myself. When am I going to need five chest seals?”

He heard the breach and then began to see the children being carried out amid the smoke of the brief but intense gunfire, he said.

He went to help a Border Patrol medic who was treating a girl who had been shot in the chest. She said she began checking her legs for injuries when she heard her colleagues ask for a seal on her chest. In the chaos of the response, everything had been taken.

Springer said they covered the girl’s wounds with gauze, lifted her onto a board and repeatedly told others to secure her head while they moved her, though he later believed the young victim was too small for the carrier.

“I don’t think they secured her head because she wasn’t tall enough to secure her head,” he said. And although the girl was thought to be alive when she was taken from the classroom, she did not survive, she said.

When she went back inside, the hallway lined with signs celebrating the end of the school year had been transformed. “You could smell the iron, there was so much blood,” she said.

Body camera footage shows the officers before they entered the classrooms. The halls would soon be covered in blood. (Credit: Texas House of Representatives Commission of Inquiry)

Back outside, Shoemake, of Uvalde EMS, had put the first victim in his ambulance to hide her from the crowd of anxious parents frantic for information, when they pulled out another girl. She saw an unattended ambulance from a private company with its door open and no stretcher, she said.

“I had her put on the floor of that ambulance and started caring for her there. Then, while I was treating her, they brought me two more 10-year-old boys, so I put one on the bench and one in the captain’s seat.”

Shoemake’s colleagues, including Kathlene Torres, came to help and loaded the girl onto a stretcher and into another ambulance, working to save her life, as they first thought a helicopter would take her and then take her to the hospital themselves, they said.

Torres told a DPS officer that the girl was seriously injured, but still managed to share her name and date of birth. She was Mayah Zamora, who would spend 66 days in the hospital before being able to return to her family. “I can still hear her voice,” Torres said.

At least two of the paramedics had been at Robb’s earlier in the day to watch the award ceremony for their children. One of them, Virginia Vela, had seen her fourth grade son at a 10 a.m. ceremony and then, two hours later, was cornered in the parking lot of the funeral home across the street from the school with her husband and other parents who were being held by officers.

Vela told the DPS investigator that she was recognized as a local EMT and was allowed into the funeral home to treat some children who had been injured climbing through the windows to get away from the school.

As he approached the school to help the other EMTs, he saw the first victim being pulled out, a child who was dead, he said.

“I thought it was my son,” he said. “Once I saw his clothes, I knew he wasn’t my son, but fear… ran through my body.”

More children came for emergency medical treatment.

“One of the children I had in the unit was shot in the shoulder. The student who was helping to get up from the side of the unit had bullet fragments in his thigh,” he said. “And then we had another student with his fingers blown off. And she came and went. We were trying to get her oxygen and keep her alive. And I realized that those were my son’s classmates and my son would not go out.”

Vela opened the ambulance to see if they brought more children. And finally, she saw her son run out of the school.

“I didn’t even run to him. I didn’t go looking for it. What I was thinking was ‘run buddy… get away from that school, just run to the bus,'” she said. “I grabbed my phone and called my husband and my husband said, ‘I see him, I see him, he’s getting on the bus, okay’. And I said, ‘Okay, but I have to stay here with these students.’ And I hung up and kept doing my job.”

Vela told DPS that she remembered a little more of the day after she knew her son was safe, but it was still a blur as she worked with Shoemake and the others, writing a child’s vital signs on her arms and getting them on their way: Load and go, load and go.

And once the emergency work was over, he had an important question.

“I asked my partner: ‘Did I freeze? I helped you?’ She says, ‘Yes, girl. You were like jumping from unit to unit, helping everyone that came out,’” Vela said. “And I was like, I need to know this. I need to know that I continued to do my job.”