A new museum dedicated to the often-silent trauma of German civilians forced to flee Eastern Europe at the end of World War II opens next week after decades of heated debate.

Perhaps reflecting what its founders call their delicate “balancing act”, the new institution in Berlin carries the unwieldy name of Documentation Centre for Displacement, Expulsion and Reconciliation.

Between 1944 and 1950, some 14 million Germans fled or were ejected from today”s Poland, Russia, the Czech Republic, Hungary, the Baltic states, Romania, Slovakia and the former Yugoslavia.

Escaping the Russian army and later pushed out by occupying powers and local authorities, an estimated 600,000 Germans lost their lives on the trek.

The displaced millions included people who had settled in Nazi-occupied territories as well as ethnic Germans who had lived for centuries as minorities in other countries.

Seventy-six years after the conflict’s end, director Gundula Bavendamm said Germany was finally ready to talk about the suffering of some of its own people, while still acknowledging the unparalleled crimes committed by the Nazis.

“We are not the only country that needed quite some time to face up to painful and difficult chapters of its own history,” she told reporters at a preview of the museum before it opens to the public on Wednesday. “Sometimes it takes several generations, and the right political constellations.”

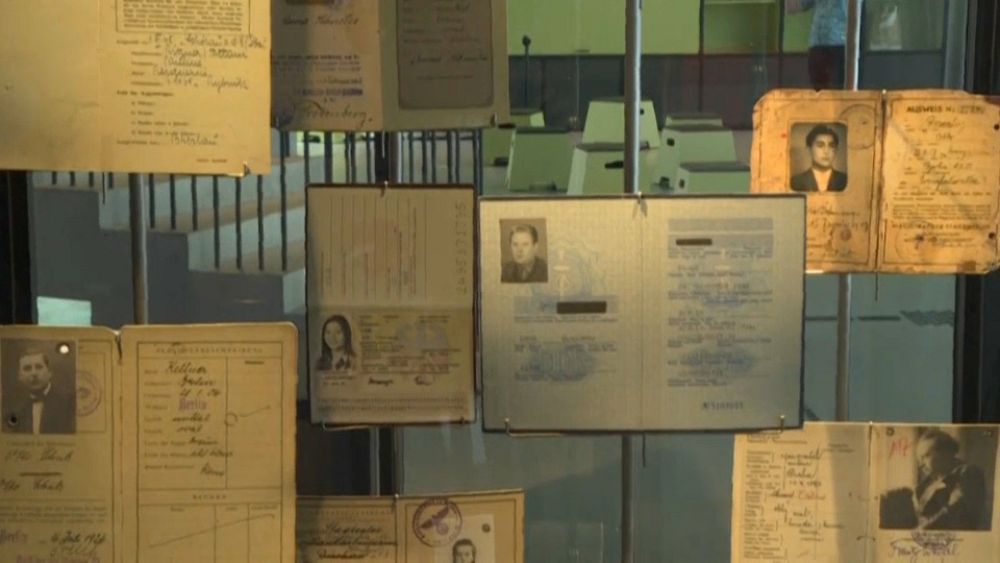

Relics from mass German exodus alongside contemporary artefacts

The 65-million-euro museum is at pains to place the Germans’ plight firmly in the context of Hitler’s expansionist, genocidal policies.

It is located between the museum at the former Gestapo headquarters and the ruins of the Anhalter railway station, from which Jews were sent to the Theresienstadt concentration camp.

Just opposite is a planned Exile Museum devoted to those who fled Nazi Germany. An estimated one-third of Germans have family ties to the mass exodus at the war’s end.

The museum presents often poignant family heirlooms dating back to this period. A haunting cross stitch with a rhyme about kitchen tidiness hangs unfinished, a dark thread still dangling from the cloth because the woman working on it suddenly had to run from advancing Soviet troops.

A girl’s leather pouch is marked with her old address in Fraustadt, now the Polish town of Wschowa: Adolf Hitler Strasse 36. It is displayed in a case near a well-thumbed Hebrew dictionary.

Keys from a villa in Koenigsberg – today’s Kaliningrad – that was vacated in 1945, placed alongside those from a house in Aleppo, Syria that was abandoned during the civil war in 2015, symbolise the enduring hope of returning home one day.

“Everything you see displayed here is a miracle because it survived the journey,” Bavendamm said.

The around 12.5 million people who made it to what would become East and West Germany as well as Austria often faced discrimination and hostility on the way.

Now decades on, the museum’s library offers assistance to families hoping to retrace their ancestors’ odyssey. Elsewhere, a “Room of Stillness” allows visitors to sit and reflect on difficult memories.

Decades in the making

A shroud of silence and shame long covered the suffering experienced by German civilians during and after the war.

Groups representing those expelled in the post-war period sometimes had links to the far right, and occasionally agitated against government efforts to atone for Nazi aggression.

Only after the Cold War and a long process of international reconciliation did incidents such as the devastating Allied firebombing of Dresden, or the 1945 sinking of the Wilhelm Gustloff ship carrying German refugees, come to be talked about.

The far right’s attempts to co-opt such events to underline notions of German victimhood also complicated efforts to find the right, conciliatory tone.

Der Spiegel has called the museum “a statement to the left and the right-wing, to Germany and abroad. It is meant to close a last remaining gap in German remembrance”.

The seeds for the project were first planted in 1999 by Erika Steinbach, an archconservative lawmaker who had voted against the recognition of Germany’s postwar border with Poland after the fall of the Iron Curtain.

An infamous Polish magazine cover depicted Steinbach as a Nazi dominatrix forcing Germany’s chancellor at the time, Gerhard Schroeder, to do her bidding.

However, Schroeder’s successor Angela Merkel recognised the necessity of the museum – albeit for different reasons. In 2008 Merkel agreed with broad mainstream support to establish a centre dedicated to a spirit of international reconciliation.

Historians from across Europe and Jewish community representatives were enlisted as advisors.