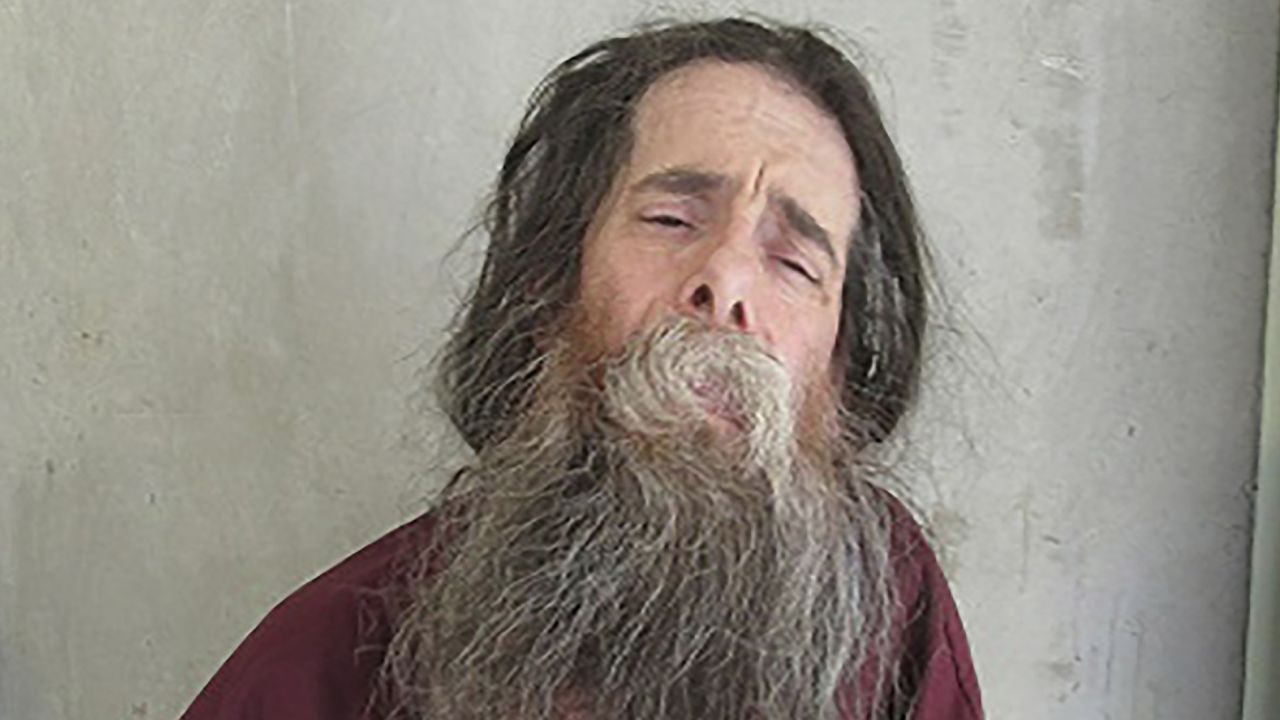

(Trends Wide) — Oklahoma executed by lethal injection Benjamin Cole, who was sentenced to death for the 2002 murder of his 9-month-old daughter, Brianna Victoria Cole. The prisoner’s execution occurred despite objections from defense lawyers who argued that the 57-year-old suffered from schizophrenia and was severely mentally ill.

The case highlighted a longstanding issue in the debate over capital punishment: how it should be applied to those with mental illness. Meanwhile, relatives of the murdered girl denounced Thursday the two-decade lapse between Brianna’s death and Cole’s execution.

The execution, the second of 25 Oklahoma has scheduled through 2024, began Thursday at 10:06 a.m. local time, Oklahoma Department of Corrections Chief Operating Officer Justin Farris told reporters. Cole was pronounced unconscious at 10:11 a.m. CT and pronounced dead at 10:22 a.m. CT.

Cole turned down one last ceremonial meal and decided not to have a spiritual advisor with him, Farris said.

Donna Daniel, Brianna’s aunt, thanked the state for carrying out the sentence and bringing justice to her late niece, whom she described as a blonde baby with blue eyes.

“She died a horrible death,” Daniel told reporters, adding, “And she gets away with it easily and gets a little injection in her arm and falls asleep to her death. It didn’t give Brianna a chance to grow up, to even have her first Christmas, to meet her family.”

When asked what family members who witnessed the execution would do now, Bryan Young, Brianna’s uncle, said: “Back to normal.”

“As normal as it can be,” added Daniel, who also told reporters: “We shouldn’t have to wait 20 years for a 9-month-old baby to get justice.”

Cole’s attorney called him a “seriously mentally ill person whose schizophrenia and brain damage” led him to murder his daughter, according to a statement. At the time of his death, Cole had “fallen into a world of deceit and darkness,” said the attorney, Tom Hird, and “often was unable to interact with my colleagues and myself in a meaningful way.”

“Ben lacked a rational understanding of why Oklahoma took his life today,” Hird said. “As Oklahoma continues its relentless march to execute one traumatized and mentally ill man after another, we must pause to ask ourselves if this is truly who we are and what we want to be.”

Cole is the second death row inmate sentenced to death in the series of more than two dozen executions that the state of Oklahoma intends to carry out through 2024, a series that critics have condemned in the midst of history. state of failed lethal injections.

The procedure for Cole on Thursday was “smooth and uncomplicated,” Farris told reporters.

His last words were an incoherent, often nonsensical stream of consciousness, sometimes referring to the “Lord” and “Jesus” and sometimes too quiet to make out, journalists who later witnessed them said.

Cole prayed for the state of Oklahoma and the United States, also saying, “I forgive everyone I’ve done wrong,” recalled Sean Murphy of the Associated Press.

Both Murphy and Nolan Clay of The Oklahoman newspaper, each of whom indicated that he has witnessed multiple executions, described Cole’s execution as similar to others they had seen.

Cole’s lawyers insisted that he should not be executed because his mental condition, magnified by childhood exposure to drugs and alcohol, substance abuse problems, and physical and sexual abuse, had deteriorated so much that he was unable to be executed, according to a clemency petition.

On Wednesday, the US Supreme Court rejected Cole’s request to stay the execution. Cole’s attorneys also unsuccessfully petitioned a state appeals court to force the inmate’s warden to refer his case for review to the district attorney to initiate a competency hearing.

Cole was living in a mostly “catatonic” state, attorneys said.

The facts of Cole’s case compelled the state to spare his life, his attorneys told parole board members in recent months, though arguments failed. They pointed to “evolving standards of decency”, including public polls showing disapproval of executions of the mentally ill.

Oklahoma had “an opportunity to display courage, follow these standards, and be on the right side of history by prohibiting the execution of Benjamin Cole, a seriously mentally and physically ill person.”

In a 1986 ruling, the US Supreme Court declared the execution of the seriously mentally ill unconstitutional, and Justice Thurgood Marshall wrote: “It is no less abominable today than it has been for centuries to exact the life of someone whose mental illness prevents him from understanding the reasons for the penalty or its implications”. And in Oklahoma, state law makes it illegal to execute someone who is found to be insane.

Cole, who was diagnosed with schizophrenia and had brain damage associated with Parkinson’s disease, was living in a mostly “catatonic” state, barely speaking to anyone, including his own attorneys, according to his clemency petition. After years of near-total isolation in the Oklahoma State Penitentiary, he used a wheelchair and lived in what a clinical psychologist described in the clemency petition as his own “mental universe,” without understanding the legal proceedings surrounding his death. imminent execution.

“Benjamin Cole is incapacitated by his mental illness to the point of being essentially nonfunctional,” Hird said in a statement after an Oklahoma judge ruled this month that Cole was fit to be executed.

“His own lawyers have not been able to have meaningful interaction with him for years, and the staff who interact with him every day in prison confirm that he is unable to communicate or take care of his most basic hygiene. He just doesn’t have a rational understanding of why Oklahoma is seeking to execute him.”

Oklahoma Attorney General John O’Connor praised the parole board’s September vote to deny clemency in a statement, noted that Cole’s conviction and sentence had been upheld on appeal, and dismissed questions about his mental illness.

“Although his attorneys state that Cole is mentally ill to the point of catatonia, the fact remains that Cole fully cooperated with a mental evaluation in July of this year,” the attorney general said on September 27. “The evaluator, who did not was hired by Cole or the State, found Cole fit to execute, and that ‘Cole does not presently show substantial overt signs of mental illness, intellectual disability, and/or neurocognitive disability.

The murder of Brianna Cole

Cole was convicted of the brutal murder of Brianna in December 2002, according to the attorney general’s office, when her screams interrupted him while playing a video game.

Cole grabbed his daughter’s ankles while she was face down and forced them onto her head, breaking her spine and causing her to bleed to death, according to a probable cause affidavit. Cole later returned to her video game when her daughter died, O’Connor said.

Cole admitted in a taped confession that he caused his daughter’s fatal injuries, according to his clemency plea, and told police he would “regret his actions for the rest of his life.”

Before his trial, prosecutors offered him a plea deal that would have resulted in life in prison without parole. But Cole, whose mental state was already deteriorating, refused to accept it, a “total act of irrationality against self-interest,” his petition said.

Cole wanted the case to go to trial because, he told his attorneys, it was “God’s will” and “his story … would transform Rogers County, and allow God to touch hearts and allow Benjamin to walk away from everything as a free man”.

Cole had not yet been diagnosed with schizophrenia, but his trial attorneys called twice for competency evaluations, arguing that his religious delusions made him irrational and, as a result, he did not understand legal proceedings. Still, he was declared competent to stand trial.

Cole’s attorneys recently argued that his attorneys at trial, along with the judge and sheriff, recognized the prevalence of his mental illness when the man sat in court “literally not moving a muscle for hours on end with an open Bible.” in front of him on the table,” according to the petition. Cole did not testify and was sentenced to death.

Cole’s struggles with his mental health date back to his early childhood, growing up in a junkyard surrounded by “rampant” drug and alcohol abuse, his petition said. Encouraged by the adults in his life, Cole began drinking when he was a young child, he said, and one of Cole’s brothers testified that they would get high by snorting gasoline when Cole turned 10. Cole also endured years of verbal, physical and sexual abuse, the petition states.