First it was loo roll, then personal protective equipment, baking ingredients, fruit- pickers and, latterly, testing kits.

With every major shortage of every important commodity during this pandemic, the patience of the British people has been tested to the limit. Yet, somehow, we have managed to muddle through.

Until now. For we may be fast approaching a shortage that really could do for this Government.

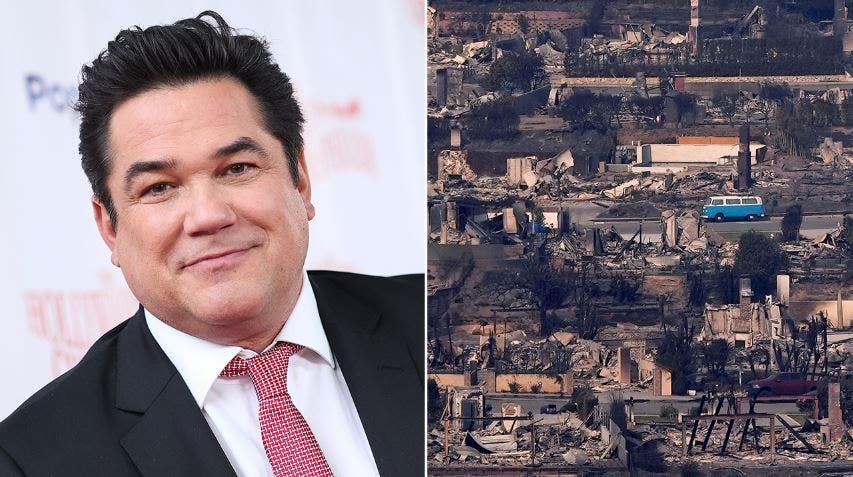

In short, two months from now, large parts of the country could be facing a Christmas with all the trimmings — but no turkey. Robert Hardman is pictured above at Copas Turkey Farm

Indeed, I fear that the mere mention of it may be enough to incite public disorder. However, given that there is still time to resolve this crisis, this is no time to stay silent.

In short, two months from now, large parts of the country could be facing a Christmas with all the trimmings — but no turkey.

A series of Covid-related developments — including a serious shortage of skilled migrant labour and the fact that very few people are either going abroad or eating out this Christmas —mean that demand is going in one direction and supply in the other. And that points inexorably towards a nationwide run on our favourite bird.

Orders are already well ahead of the same stage last year here at the Copas family’s Berkshire farm.

The Copas family — Tom runs the business with his wife, Verity (pictured together above) and three sisters — sell only to independent butchers and directly to the public, so they have their ear to the ground

Around 32,000 birds are having a high old free-range time ahead of what third-generation boss Tom Copas, 36, calls ‘the crunch’, following which these 600 broad acres of paddocks, cherry orchards and barns will suddenly fall silent.

At present, however, there is an incessant chorus of ‘gobble-gobble’ plus the odd tinkle of tambourine — these birds actually have their own musical instruments.

The Copas family — Tom runs the business with his wife, Verity, and three sisters — sell only to independent butchers and directly to the public, so they have their ear to the ground. This year, several patterns are emerging.

‘Not so many people will be on holiday or eating out. They’ll cook at home,’ says Tom.

‘And we are going to see less ‘home and away’ fixtures, where families might spend Christmas with one side of the family one year and another the next. This year, both sides of the family will want their own turkey.’

Verity has been touched by the number of regular customers getting in touch to wish them well through the pandemic. ‘After the year that many people have had, they are determined to have a proper Christmas and that means a proper turkey,’ she says.

The National Farmers’ Union says that Britain usually eats around ten million turkeys at Christmas, with just over six million of them ‘farm-fresh’ birds reared at home. The rest are mainly frozen imports and special cuts such as crowns and breasts.

This year, though, all the indicators are that we are going to need many more birds from an industry which could be missing up to half its workforce. Hence the looming crisis.

A turkey-free Christmas? We may as well block up the chimney, leave the Christmas tree in the forest and tell the Queen not to bother come 3pm on December 25!

A further consequence of the pandemic is that the Government’s rule-of-six limit on family gatherings means that many families will want a much smaller bird.

The entry-level model on many farms will weigh around four kilos (9 lb) — enough to feed eight to ten adults.

According to the British Poultry Council, there will be some producers who see no point in spending more money on more food and electricity to fatten up a bird that has already exceeded market size for these reduced Christmas gatherings

According to the British Poultry Council, there will be some producers who see no point in spending more money on more food and electricity to fatten up a bird that has already exceeded market size for these reduced Christmas gatherings.

They may want to slaughter their birds now and stick them all in the freezer, especially with a major manpower shortage on the horizon.

Turkey consumption in the UK (unlike the rest of Europe) is driven by a single day in the calendar.

That means the industry is heavily reliant on temporary staff for a hectic process of slaughtering, plucking, eviscerating and packing millions of birds in a matter of days. Farm-ageddon for the turkey trade is just weeks away and, as ever, the UK looks to Eastern Europe.

‘You really do need people trained in butchery, who know what they’re doing — for welfare, for safety and so on,’ says Aimee Mahony, chief poultry adviser to the National Farmers’ Union. She has around 270 members producing fresh, ‘farm-gate’ home-grown birds for the domestic market.

Between them, they rely on around 8,500 part-time staff, half of them Eastern European poultry workers who would normally take a fortnight’s holiday and book a flight to the UK to help out.

It’s good money, many are old friends and everyone gets home in time for Christmas. However, if they will face two weeks of quarantine on the way in — as is currently the case — then they simply won’t come. And that would be disastrous, since many farmers just won’t be unable to process their birds in time for Christmas.

So they are lobbying the Government with a simple request: to be granted exactly the same exemption ministers have already granted to the fruit industry.

Back in late summer, Eastern European workers were allowed to come to the UK and spend their quarantine period picking fruit, provided they remained in a bubble on the farm. Poultry farmers merely want the same deal.

‘The next few weeks are going to be crucial,’ says Aimee Mahony.

Tom Copas is praying that the exemption comes in time for the dozens of workers who have been travelling to Cookham, Berkshire, from Poland and Romania each winter for years. Their digs await.

A while back, his father, Tom senior, had the bright idea of buying up some of the accommodation units that were used by the workers who had built the Channel Tunnel.

His barns are all spotless and ready to go and ‘bubbles’ have been planned. He has even arranged pre-departure Covid tests and private ‘bubbled’ buses across Europe for his seasonal workers, but he still can’t confirm things.

Unlike the big industrial producers who go for ‘wet-plucking’ (whereby a carcass is dunked in scalding water and plucked by machine), traditional farms like this prefer ‘dry-plucking’, much of it by hand.

It produces superior meat, better flavour and allows the turkey to hang properly in cold storage for 14 days. But it requires expertise and it needs to happen on time.

‘It is bang or bust in this business,’ Tom explains cheerfully, ‘but we’ll make it work. We have to!’

There is no chance of an early demise for any of the birds on the Copas family’s farm.

‘You have got to let the bird grow properly for up to 26 weeks. Otherwise, you don’t get the stores of fat which make it juicy,’ says Tom. ‘People want a proper turkey, not a bag of bones.’

After all the grim uncertainty of 2020, can we not at least feel confident of a turkey on the table on Christmas Day? This industry, unlike others, is not demanding gazillions from the Government. Turkey farmers merely want the same rights as fruit farmers — and fast

If you had to be a turkey anywhere, this seems a pretty good perch. The birds are divided according to breed and size, ranging from the Devon Bronze, which might weigh in at four-and-a-half kilos (10 lb), to a hefty 10 kg (22 lb) Wirral Black.

Every field is surrounded by two fences, one with a thick mesh and one electric.

They are not there to keep the turkeys in, but to keep the foxes and mink out. Hence the sight of some faintly bemused alpacas.

‘A few years ago the foxes killed 350 birds in one week alone, mostly for fun, and you can’t keep dogs with turkeys. Then someone told me that alpacas have a great guarding instinct. They all get on very well and the foxes stay away.’

Turkeys love to peck at anything shiny — they even peck the buckles on my boots; hence the tambourines and children’s xylophones hanging on string.

It all helps to keep the birds calm. If they are suddenly spooked, they can stampede, which leads to bruising, injury and even suffocation.

For the same reason, all the fields have tall crops to make the birds feel safe from anything overhead.

Further pampering is due next week when Tom begins ‘firework training’, letting off a few controlled pyrotechnics so that the birds are not suddenly freaked out by any Bonfire Night displays.

So, any top tips for the perfect turkey? ‘Breast side down under loose foil for three-quarters of the time, and then turn it over with the foil off,’ says Tom. ‘And always let it stand for 45 minutes.’

I am already feeling peckish — and a little worried, too.

After all the grim uncertainty of 2020, can we not at least feel confident of a turkey on the table on Christmas Day?

This industry, unlike others, is not demanding gazillions from the Government. Turkey farmers merely want the same rights as fruit farmers — and fast.

Anything else, frankly, is gobbledygook.