Vallentuna, Sweden (CNN) — Drive north of the Swedish capital for about half an hour and you’ll reach the lakeside district of Vallentuna, a pleasant community with cobblestone churches, picnic areas and playgrounds.

It’s also a journey deep into Sweden’s ancient Viking past.

Scattered among Vallentuna’s greenery are dozens of mystical runestones that form the gateway to a 1,000-year-old Viking civilization now believed to be one of Scandinavia’s most significant historic sites.

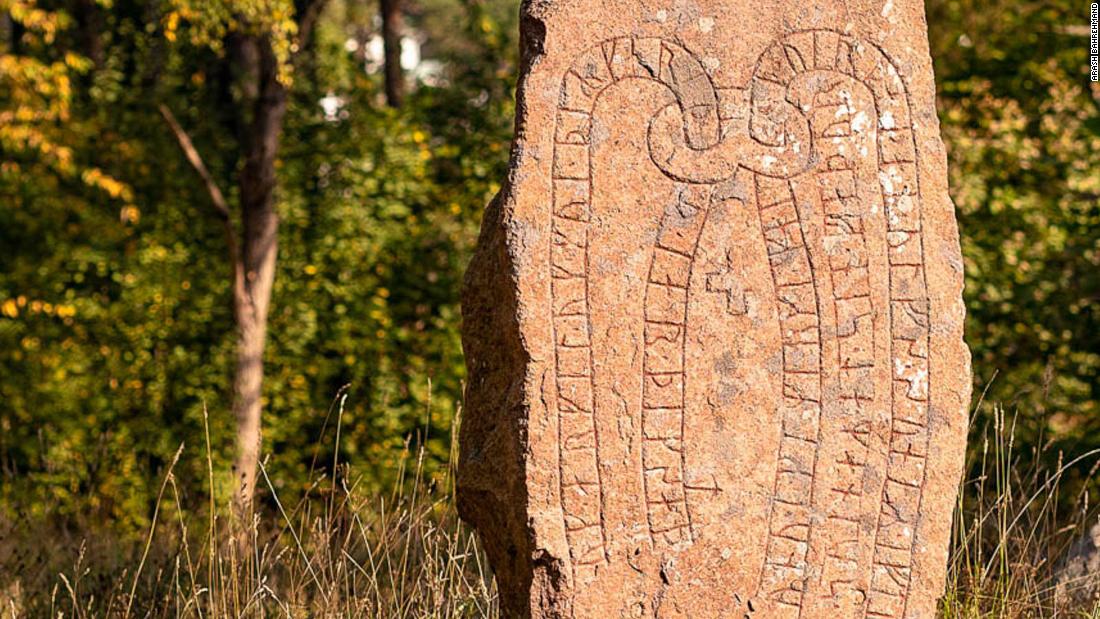

Known as Runriket, or Rune Kingdom, this collection of more than 100 Viking age runestones — ancient lichen-crusted slabs of Old Norse inscriptions — are beautiful relics that shine a light on modern Sweden’s past, revealing surprising truths about its ancestors.

Vikings are often depicted as brutish Odin-worshippers who pillaged, drank and made blood sacrifices. While there’s truth to the stereotype, the relics of Rune Kingdom actually paint a picture of devote Christian settlers on the cusp of embracing medieval lifestyles.

Among them, one man stands out — an 11th-century Viking ruler named Jarlabanke who appears in more runic inscriptions here than anyone else — largely because he seems to have been colossally self-important.

“He had many runestones made, both after others but more famously after himself, something that was quite rare,” says Eric Östergren, a guide at Stockholm’s Viking Museum whose own long auburn beard and gray-blue eyes have a flavor of Old Norse about them.

“From these runestones, we can assume Jarlabanke’s power grew and he changed the local political landscape,” Östergren adds.

Jarlabanke’s gargantuan ego — big enough to echo through the ages — has left precious archaeological evidence of a civilization which, because Vikings mostly used wood for construction, is otherwise scarce.

The runestones created by Jarlabanke reveal the influence of his dynasty across five generations and archaeologists have been able to use them to piece together a key chapter for Viking society little known outside of Scandinavia — the arrival of Christianity.

Sweden’s first Christians

Norse code: The runestones of Runriket shed light on a little-understood chapter of Sweden’s ancient past.

Arash Bahrehmand

On the east side of Vallentuna Lake stand two formidable granite runestones that bear identical inscriptions and face each other. Measuring about 1.65 meters (5 ft, 5 in), their etchings claim they mark the original location of a bridge built by Jarlabanke.

Archaeologists believe this ancient structure was raised as a passage over marshland to a church.

The bridge — locally known as “Jarlabanke bro” — is the most common starting point to conduct a tour of Runriket, which can be done by car or on foot.

As is common with stones connected to Jarlabanke, Old Norse letters are written within the winding tail of a mythical serpent that frames a large, artistically drawn cross.

Many of the runestones at Runriket are carved with these unmistakably Christian crosses, some elaborate in design, like the two at Jarlabanke Bridge, and others with simple, shallowly engraved lines.

These are among the first Christian symbols found in Sweden. In fact, archaeologists have linked the arrival of Christianity in Sweden directly to Jarlabanke through the stones at Runriket.

“We know that they (Jarlabanke and his family) must have been the earliest Christians in this area and that Jarlabanke’s grandfather Östen traveled all the way to Jerusalem on a pilgrimage as early as the first half of the 11th century,” says Magnus Källström, a researcher at the Swedish National Heritage Board and one of Sweden’s most sought-after runologists.

The stones also tell us of an important transition in funeral practices, signaling the departure of pagan rituals in exchange for Christian burials.

“In Vallentuna’s runestones, we can document a change of culture, from a time when a burial mound was built to an embrace of more medieval customs,” Östergren says.

‘He alone owned all’

Jarlabanke’s imposing presence can still be felt across Vallentuna. If he were around today, Östergren likes to joke to visitors to his museum, the Viking “would probably upload selfies every day” to Facebook.

While there are missing pieces to the puzzle, everything known about Jarlabanke has come from the runic inscriptions on the stones.

“Jarlabanke must have been a very important and wealthy person in the vicinity of Vallentuna Lake,” observes Källström. “He built his impressive bridge and he arranged an assembly place probably close to where Vallentuna church stands today.”

Källström points to a two-sided runestone that sits alongside the Vallentuna church on a sunny hillside over the lake. It provides a fundamental clue to understanding Jarlabanke’s power.

Tracing his finger across runes partially obscured by gray and brown moss, he reads out the inscription in Old Norse, which to the untrained ear sounds a lot like a mystical spell from a J.R.R. Tolkien novel.

“Jarlabanki let ræisa stæin þenn at sik kvikvan,” he recites. “Jarlabanke had this stone raised in memory of himself while alive.

“And made this assembly place, and alone owned all of this hundred.”

Here, the word “hundred” refers to a large administrative region. According to Källström, it’s debatable whether Jarlabanke was merely a powerful landowner, or played another more significant role.

“This is a very large area and it seems impossible that all this land was in Jarlabanke’s private possession. Most probably, the verb æiga — “to own” — means something different here: that he was the chieftain for this hundred, or the law speaker or judge.”

The amount of times Jarlabanke writes his name in Vallentuna also suggests that he was quite powerful, and wanted to make sure everyone knew it.

Källström also suggests that there could have been a power struggle with his half-brother, which would explain why Jarlabanke took pains to clearly state that “he alone” ruled the area.

Still, other researchers like Östergren say that the ruthless nature of Viking politics combined with a narcissistic personality would make for a ruler that was likely more “mafia boss” than simple adjudicator.

“Jarlabanke is mentioned on 10 of these stones, and six of these he has put up in memory of himself!” Källström excitedly points out.

Messages from the past

Moreover, Jarlabanke’s love of runestones likely inspired many others in the area to follow suit in seeking political influence by paying for a craftsman to raise a runestone.

Whatever the motivation, the result was the creation of a kingdom of late Viking Age inscriptions that would endure through the centuries.

Reading the russet-colored Runic letters — some of which are similar to Latin — is one thing. Decoding the meaning of an Old Norse message is another. For this reason, there are still many mysteries left in Viking runestones still to be understood.

This year, for instance, runologists finally managed to decipher the Rok stone, Sweden’s most famous runestone.

An inscription that famously mentions Ragnarok, the Viking apocalypse, the Rok’s inscription is written in the form of a riddle that tells of a climate change event that impacted the Vikings of the ninth century.

Östergren says that Runriket is a portal through which countless more mysteries may yet be solved.

“Runriket is both a road to further knowledge for those who want to go in depth, but also for those that are just starting to scratch the surface of understanding who the Vikings really were.”