There is only one way to stop the genocide that continues unabated in Gaza, and that is not through sterile bilateral negotiations. Israel has demonstrated beyond doubt—including by assassinating Hamas’s chief negotiator, Ismail Haniyeh—that it does not care about a lasting ceasefire. The only way to stop Israel’s genocidal campaign against the Palestinians is for the United States to stop supplying it with weapons. And the way to do that is through a strong public will. Americans must make clear that they will not support any presidential candidate or political party that contributes to this crime.

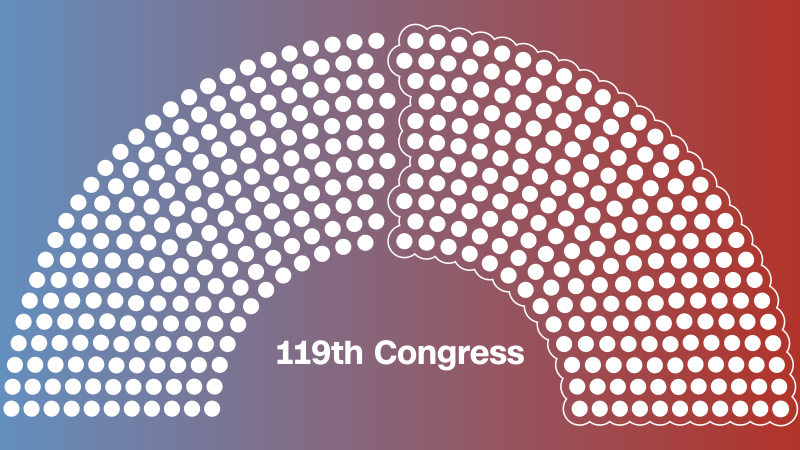

The arguments against a bipartisan boycott are well-known: that it would lead to a victory for Donald Trump, that Kamala Harris has apparently shown more sympathy than Joe Biden, that we, as few as we are, will not make a tangible difference, that we can work within the Democratic Party, that the Israel lobby—particularly the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC)—dominates the majority of Congress, and that negotiations will ultimately stop the carnage.

In short, we are powerless, and we must abandon all hope of stopping this monstrous project. We must accept as a fait accompli the sending of hundreds of millions of dollars in military aid to an apartheid state, the use of our veto in the UN Security Council to protect Israel, and the blocking of any international effort to end the mass killing. We have no choice.

Genocide, the crime of crimes under international law, is not merely a political issue, like trade agreements or infrastructure projects or charter schools or immigration. It is a moral issue that touches the very essence of humanity, the annihilation of an entire people. Any submission to this heinous act condemns us as a nation and as a species. It brings the global community one step closer to barbarism, tears apart the rule of law, and makes a mockery of every value we profess to respect.

Genocide is in a category of its own, and not resisting it with all we have is participating in “radical evil,” the evil that makes man superfluous, as Hannah Arendt described it.

The basic lessons of the Holocaust offered by writers like Primo Levi are that we can all become willing executioners. It takes little to become complicit, even through indifference or hesitation, in evil.

“Monsters exist,” wrote Auschwitz survivor Levi, “but they are too few to be truly dangerous. The most dangerous are ordinary men, who are prepared to believe and act without asking questions.”

Confronting evil, even when there is no chance of success, preserves our humanity and our dignity. It allows us, as Vaclav Havel wrote in The Power of the Powerless, to live in that truth that the powerful do not want to be told and seek to suppress. It provides a light for those who come after us. It tells the victims that they are not alone. It is “humanity’s revolt against imposed injustice” and “an attempt to recover a sense of responsibility.”

What does Havel say about us if we accept a world in which we arm and finance a nation that kills and injures hundreds of innocent people every day?

What does it say about us if we support a planned famine and poisoning of water sources, where polio has been discovered, meaning tens of thousands will become ill and many will die?

What does it say about us if for ten months we have allowed refugee camps, hospitals, villages and cities to be bombed, with the aim of wiping out families and forcing survivors into the open or into primitive tents?

What does it say about us when we accept the killing of 16,456 children, knowing that this number is certainly an underestimate?

What does it say about us when we watch Israel escalate its attacks on UN facilities, schools – including one of its own in Gaza City, where more than 100 Palestinians were killed during dawn prayers – and other emergency shelters?

What does it say about us when we allow Israel to use Palestinians as human shields by forcing documented civilians, including children and the elderly, into tunnels and buildings that may be booby-trapped, ahead of Israeli forces, sometimes wearing IDF uniforms?

What does it say about us when we support politicians and soldiers who justify the rape and torture of prisoners?

Are these the allies we want to empower? Is this the behavior we want to adopt? What message are we sending to the rest of the world?

If we don’t uphold moral imperatives, we are doomed. Evil will triumph. It means that there is no right or wrong. It means that anything, including mass murder, is permissible. Protesters outside the Democratic National Convention at the United Center in Chicago are calling for an end to genocide and U.S. aid to Israel, but inside the convention halls we encounter a disturbing conformity. Hope lies in the streets.

An ethical position always comes at a cost. If there is no cost, it is not an ethical position. It is just a popular opinion.

“But what about the price of peace?” asks radical Catholic priest Daniel Prejean, who was imprisoned for burning draft records during the Vietnam War, in his book No Barriers to Manhood. He goes on to say:

“I think of the good, decent, peace-loving people I have known by the thousands, and I wonder how many of them are so sick of stereotypes that even as they proclaim peace, their hands instinctively reach out for their possessions, their homes, their security, their income, their future, their plans; that five-year plan for studies, that ten-year plan for professional status, that twenty-year plan for family growth and unity, that fifty-year plan for a dignified life and an honorable natural death!”

“Of course, we cry: ‘Let us have peace,’ but at the same time let us lose nothing, let us keep our lives intact, let us know neither prison nor bad reputation nor severing ties.” And because we must include this and protect that, because at all costs our hopes must go according to their scheduled schedule, because it is unusual for a sword to fall in the name of peace, unraveling the beautiful and delicate web that our lives have woven, because it is unusual for good men to suffer injustice, for families to be separated, for good reputations to be lost, because of all this we cry for peace, and then we cry for peace, and there is no peace!”

“There is no peace because there are no peacemakers. There are no peacemakers because peacemaking is at least as costly as warmaking. It is at least as urgent, at least as disruptive, at least as likely to bring shame, imprisonment, and death in its wake.”

The question is not whether resistance is a practical option. The question is whether resistance is right?

We are commanded to love our neighbor, not our tribe. We must believe that good attracts good, even if the tangible evidence around us is bleak. Good is always in action. It must be seen. It does not matter if the wider society is harsh. We are called to challenge through acts of civil disobedience, to disobey the laws of the state, when those laws conflict, as they often do, with the moral law.

We must stand, at all costs, with the oppressed and downtrodden of this land. If we fail to take that stand, whether against the abuse of military police, the inhumanity of our vast prison system, or the genocide in Gaza, we become complicit in a great moral crime, we become partners in an evil that threatens to dehumanize our world.

The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of Al Jazeera Network.