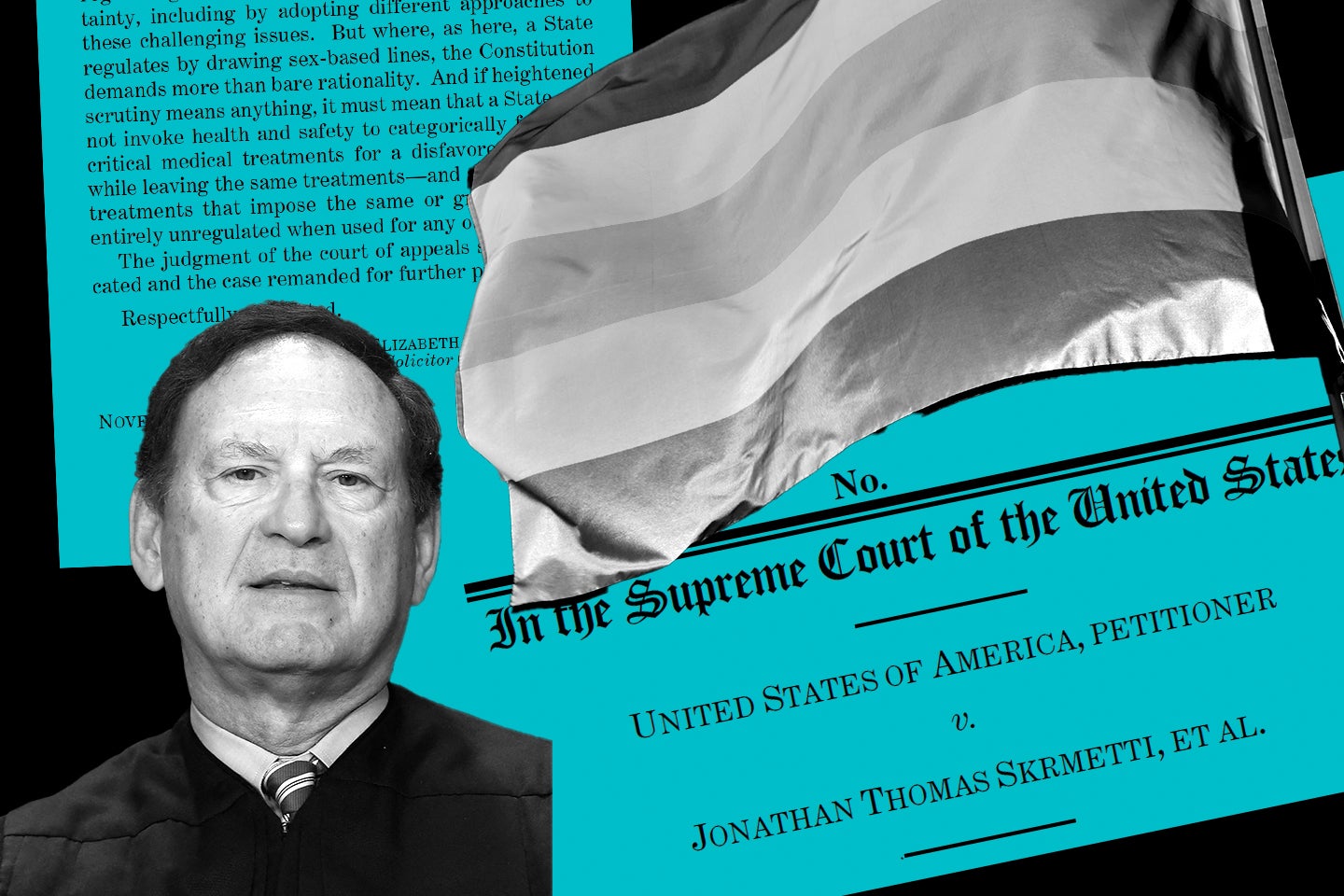

On Dec. 4, the U.S. Supreme Court will hear arguments in what is likely to be the most important trans rights case in history. It will have knock-on effects for civil rights jurisprudence that will affect the freedoms and protections of LGBTQ+ Americans, women, medical providers, and parents’ rights to raise their children without interference from the state. Tennessee’s SB1 bans surgery, puberty blockers, and hormone treatment for the purpose of gender transition for people under 18. On Amicus, Dahlia Lithwick spoke to Chase Strangio, co-director of the American Civil Liberties Union’s LGBTQ and HIV Project, who will argue United States v. Skrmetti. Strangio will be the first openly trans lawyer arguing at the high court. Their conversation has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

Dahlia Lithwick: After Dobbs came down, you warned on this podcast about the ways the decision to overturn Roe had just rocket-fueled anti-trans legislation across the country. I would love for you to just remind listeners why Dobbs was never just about abortion and how it connects to the Tennessee ban in Skrmetti.

Chase Strangio: They’re connected for so many reasons—whether you look at the equality thread or the autonomy thread in Dobbs, this is about structural efforts to impede people’s abilities to make decisions for themselves. The way in which Dobbs opened the door in particular for these anti-trans bans is that first they revitalized this case that was not talked about for a long time—although we know Justice Ginsburg hated it—Geduldig v. Aiello. This was the case in which the court said that restrictions on benefits related to pregnancy are not sex discrimination. The court allowed this idea to sit dormant for quite a while, but it was reactivated by Justice Alito in Dobbs. So now, when we are talking about things related to medicine, or health, or areas where we can claim that biological differences between men and women justify some differential treatment, we see the erosion of the protections we have worked so hard to build for sex-based protections under law.

In the two and a half years since Dobbs was decided, people who have long wanted doctrinal openings to roll back antidiscrimination protections have found a group of people whom there is more public support to target, and they’ve used that to open the door to big possible doctrinal gaps in how everyone can be protected from sex discrimination. I see this happening very strategically.

Within a week of Dobbs being decided, it was cited in every single anti-trans-related case we were litigating. And it was cited for the proposition that in essence, special deference is owed to legislatures when they are regulating in the area of medicine when it deals with sex-based differences between men and women. If we take a step back and look at this moment we are in, and the obsession with trans people during the 2024 elections, it wasn’t really about trans people. What it was about—the organizing theme—was about gender roles more broadly. They are using these attacks on trans people to re-entrench old notions of what is the proper role of men and women in society.

I’m struck by how the two abortion cases before the court last year were in so many ways not about abortion per se, they were about physicians and their rights, and what kind of care they could give. And it is so striking to see a case like Skrmetti that’s essentially saying, “We don’t care what the parents think or what the doctors think.” It really is amazing that just as the parents are always right until they’re wrong, so too physicians—they’re always right, until they’re wrong.

The throughline is this deep governmental trust in and reification of parental roles and physicians’ roles, until and unless those parents and physicians make decisions the state disagrees with. It’s not just an entrenchment of gender roles, it’s also this notion that doctors are the only important autonomous actor in the abortion context in both cases last year—but now, in Skrmetti, they’re just irrelevant. They’re wallpaper.

There’s this stunning thing that we’ve seemingly just accepted, as a matter of public discourse, that not only are physicians wallpaper, they’re part of this vast and far-reaching conspiracy to provide harmful care.

We’re talking about care that is supported by the American Academy of Pediatrics, the Endocrine Society, the American Medical Association. The doctors providing this care are at the most preeminent research institutions in this country, yet somehow the argument is they’re all conspiring to provide harmful care to minors.

If we take a step back, that is quite a conspiratorial argument, and however people may disagree about, or feel discomfort about this, these are still good-faith parents and doctors trying to do right by their patients and their children. But we’ve somehow allowed this conspiracy to fester that actually everyone is just trying to provide harmful care, which is just absurd.

You just listed a tiny number of the amicus briefs on your side from medical and mental health groups and serious scientific entities. This is not something they haven’t thought deeply about. All these professional organizations are on one side, and then, on the other side, the Tennessee brief is teeming with weird deep-state conspiracy theorizing. I worry because we have seen junk science and bad data infiltrate court doctrine and make its way into opinions that then get cited as though that junk science is real.

It’s really scary, and I think it’s also a function of the fact that the courts no longer really care or look at the factual findings of the district court—they will just pull out the latest newspaper article that they see. There is an actual purpose to testing the evidence and seeing whether it holds up, because when we’ve actually gone to trial in these cases, and these witnesses are cross-examined, they have admitted they’re exaggerating, accepted that there’s no underlying scientific support for claims they’re making, pointed to the fact that perhaps it is speculative or based on internet searches or Reddit sites.

This is why, when we look at the outcomes of these cases in the district courts—where the judges are the closest to the evidence—you have an almost unanimous set of holdings when heightened scrutiny is applied, that these laws [like SB 1] just don’t hold up. When you get more detached from the evidence and it becomes more about vibes, for lack of a better word, it becomes very untethered to what is actually going on, which allows people to say things like “Well, there’s no long-term studies.” There are long-term studies. There are studies that are tracking people for periods like six years, which is extraordinarily long in pediatric medicine. This medical research has been provided for decades—that isn’t “new” in medicine. I think about all of the innovations we’ve witnessed even in my 12-year-old child’s lifetime. So I think that so much of this is distortion and out-of-context polemics.

And this is, again, a callback to the mifepristone case where the challengers were making claims as though no one has ever attempted to use these medicines before, even though there was decades of research.

If there is a thematic, background set of principles that can come forth in our argument, it is that this is not the federal government displacing Tennessee. This is Tennessee displacing the loving, reasoned, painstaking decisions of parents who are trying to do right by their children. Children who were in anguish, and are now doing better, because of the health care Tennessee now bans.