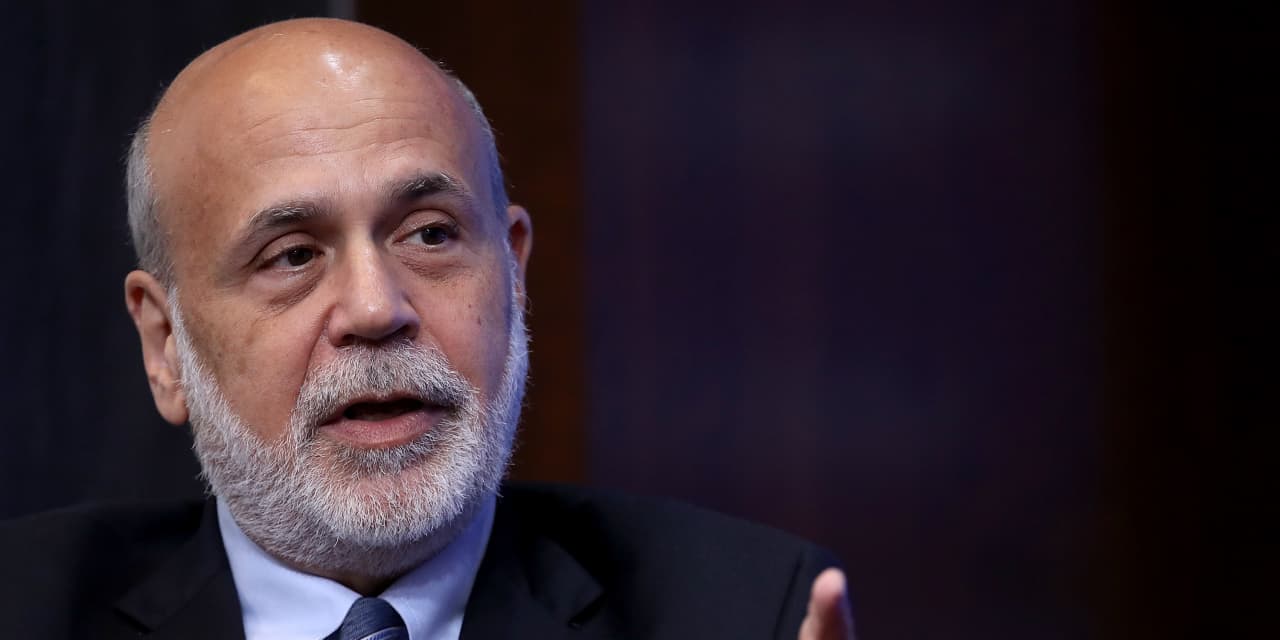

The Nobel Memorial Prize awarded to Ben Bernanke, Douglas Diamond and Philip Dybvig is controversial, to say the the very least.

Mainstream economists are usually delighted that the Nobel Committee has at last honored exploration into banking companies and their fragility. But heterodox economists who have used several years making an attempt to transform prevailing beliefs about banking and finance are spitting blood.

I normally desire to sit on the fence when it comes to fights between different branches of economics. But this time, I am firmly on the side of the heterodox economists. I do not imagine this prize is deserved. No, I would go even further. I believe it is actively harmful. It confers authority on products that misrepresent how financial institutions in fact function, and will make it a lot more challenging for heterodox economists — which includes the brave scientists at the Lender of England who have done so considerably to advance comprehension of modern-day monetary economics — to counter the pervasive myths about banking and finance that have way too usually led to damaging coverage errors.

The design of banking beloved of mainstream economists states that financial institutions “channel savings” from homes to corporations. Households make deposits, which they are capable to withdraw on demand banking companies “lend out” a proportion of those deposits to effective enterprises for very long-time period financial investment. Banking companies are assumed to be purely passive intermediaries, and as a outcome, are often omitted from financial models.

The Nobel Committee’s explanatory paper justifying the award uncritically repeats this model:

“Financial intermediaries these as banking institutions and mutual money exist … to channel money from savers to traders, receiving resources from some buyers and working with the funds to finance other folks. They also make it doable for the borrower to have a long-term funding arrangement at the same time as creditors can withdraw the dollars they lent on demand.”

It then points out how the do the job of the a few prize winners illuminates equally the importance of financial institutions to the macroeconomy and their inherent fragility.

Diamond and Dybvig’s paper on financial institution operates spawned an total literature on fiscal frictions. Bernanke’s work attracts on theirs and adds insights into the hyperlink concerning credit history and economic general performance, even though only for financial downturns — he mainly ignores credit rating booms, with, as we shall see, regrettable consequences.

But all their work depends on the “pure intermediary” model of banking. And we now know that this model of banking is dangerously wrong. It omits the leveraging impact of financial institution credit creation. This is the vital attribute of the credit score booms that generally precede disastrous collapses like the Great Depression and Great Recession.

Types that disregard bank credit generation, or worse, omit financial institutions fully — as Bernanke’s paper with Gertler and Gilchrist on how credit score markets propagate shocks by means of the overall economy does — are unable to probably demonstrate how economic crises occur and why they are so devastating.

As Mervyn King, governor of the Lender of England, ruefully observed in 2012: “There is no doubt that financial frictions these types of as uneven details, credit constraints, and expensive monitoring of debtors, to name but a number of, are an important portion of the tale of how crises transpire and why they affect on output. But those people styles do not present a convincing account of the gradual develop-up of financial debt, leverage and fragility that characterizes the operate-up to monetary crises.”

Belief that banks merely “channel” financial savings to borrowers, relatively than actively making buying ability through lending, led central bankers to ignore the develop-up of leverage prior to the Excellent Economic Crisis. And it also led central bankers and governments to mishandle the restoration. In its place of supporting homes and enterprises, they threw dollars at banking institutions. I regard this as a person of the best coverage faults of all time.

In the course of the Great Economical Crisis, banking companies stopped lending. Bernanke, the chairman of the Federal Reserve at the time, understood a unexpected halt in lender lending was a important contributor to the Excellent Melancholy, so, apprehensive about a further Depression, he made a decision he experienced to get banking institutions lending again. The mainstream model of banking claims that the far more money financial institutions have, the a lot more financial loans they will make. Of course, therefore, the greatest way of avoiding a melancholy was to give banking companies funds. This was the original rationale for quantitative easing (QE). It was intended to make banks lend.

But Bernanke did not understand that homes and businesses were being so above-leveraged, they did not want to take on much more personal debt. And nor did he fully grasp that banks didn’t want to lend.

Banking companies lend when the threat is low and the returns significant. In a damaged financial state with a gloomy outlook, there is not significantly incentive for banking companies to lend, having said that substantially cash you throw at them. Banking companies were being also under tension from regulators to minimize their pitfalls, clear up their belongings and construct their cash buffers. None of this was remotely consistent with raising lending. So inspite of mammoth QE, they didn’t lend.

Quite a few several years immediately after the Fantastic Financial Disaster, bank lending was even now significantly underneath what it had been just before it, and mainstream economists were scratching their heads asking yourself what had gone improper. Their styles explained all that QE income need to have sent bank lending to the moon.

We now know that QE functions not by stimulating bank lending, but by supporting asset charges. In the quick aftermath of the Great Fiscal Disaster, this quick-circuited a disastrous financial debt deflationary spiral and almost certainly did prevent a next Fantastic Despair. As a final result, Bernanke has been credited with “saving the earth.” But this was a lot more by accident than structure. What he was essentially striving to do was blow up another credit score bubble. We know this, mainly because it is what his educational work recommends. The perform for which he has been presented a Nobel prize.

Uncontrolled lender lending this kind of as that which preceded the Excellent Money Crisis isn’t normal. Central banks shouldn’t inspire it. And economists shouldn’t get Nobel prizes for recommending it.

Bank lending in fact recovered when the housing industry did. This is rarely astonishing, because banking companies currently typically lend against real estate collateral, and most of that is household home. It was the 2008 household selling price crash that stopped bank lending in its tracks. Had governments and central bankers understood this, they would have supported homes to stop defaults and foreclosures on home loans, not thrown insane quantities of revenue at financial institutions. And we might have had a a lot shorter and much less devastating economic downturn.

The Terrific Economic downturn uncovered fundamental flaws in the operate of all 3 prize winners. All a few unsuccessful to identify in their models the leveraging mother nature of financial institution credit development and the procyclicality of financial institution lending. Failure to understand and “lean against” the fragility caused by extreme leverage is what built the Wonderful Recession so disastrous. And faulty beliefs about the functions and incentives of banking institutions triggered plan problems that resulted in a decade of stagnation.

I do not recognize why the Nobel Committee has picked out to reward people today who received points so disastrously wrong.

Frances Coppola writes the Coppola Comment blog and is creator of “The Circumstance For People’s Quantitative Easing.” She worked in banking for 17 many years and obtained an MBA at Cass Business School in London, the place she specialized in fiscal-risk administration.