(Trends Wide) — Pride these days is synonymous with rainbow-flag-saturated celebrations of the LGBTQ community.

It’s easy to forget its solemn origins with a march commemorating clashes between police and protesters outside a New York gay bar, the Stonewall Inn.

Media coverage of what is now known as the Stonewall riots reflects the homophobic attitudes of that era. In the late 1960s, in most US states it was still illegal to be gay, not a single law protected gays from discrimination, and there were no openly gay politicians or pop culture icons.

In reality, Stonewall spurred a generation of activists to form a massive civil rights movement. But many of those people are no longer here to tell us their story of what happened.

To pin down what we know, Trends Wide spoke to three people. David Carter spent 10 years researching and interviewing witnesses for his book “Stonewall: The Riots That Sparked the Gay Revolution.” Eric Marcus is the creator of the “Making Gay History” podcast, which includes interviews with the late Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera, pioneering transgender activists. Robert Bryan joined the crowd outside the Stonewall Inn on June 28, 1969, when a police raid took an unexpected turn.

- Look: This is the story of the rainbow flag and its meaning

This is what they had to say.

What was the Stonewall Inn?

The Stonewall Inn opened as a gay club in 1967 in the heart of Manhattan’s bohemian Greenwich Village neighborhood. Despite the increasing winds whipping the nation, New York was famous for its strict enforcement of anti-gay laws that made it dangerous for homosexuals to congregate in public, let alone in a bar.

The mob stepped in to reap the benefits. To get around state regulations that prohibited homosexuals from serving alcoholic beverages, mobster “Fat Tony” Lauria operated the Stonewall Inn as a private club, taking his name from the previous diner so as not to have to change the notice.

Stonewall wasn’t the only gay bar in Greenwich Village, and it wasn’t the nicest. It had no running water and its windows were boarded up so no one could see inside. The drinks were watered down and overpriced.

But none of that mattered to the customers because it was one of the few places where they could dance.

Robert Bryan went to New York in 1968 for the “pretty boys dancing” at Stonewall. He says most of the clientele was like him: gay, white, and cisgender (meaning people whose gender identity aligns with the sex they were born with. The opposite of cisgender is transgender).

Trans people were occasional customers, but at the time, they self-identified as drag queens or transvestites, not transgender. And they rarely dressed in full regalia, considering not only street harassment, but also a law that prohibited wearing more than three items of clothing associated with the opposite sex.

Robert Bryan in August 1969.

“At first it was just a gay men’s bar. And they wouldn’t let any women in. And then they started letting women in. Then they let drag queens in,” Johnson said in a 1979 interview with Marcus.

Because it served gay customers, police raids were common. Management often bribed the Police to give them advance notice of raids so they could turn on the lights and disrupt the dance, which could risk arrests.

But there was no bribery the night of the raid that sparked the six-day uprising.

How did the riots start?

By the late 1960s, the gay rights movement was gaining momentum in the United States.

Local chapters of the Mattachine Society organization, which began in 1950, provided a community for gay men and forums for public discussion. The Daughters of Bilitis, which began in 1955, offered a similar support network for lesbians.

Before the Stonewall riots, members of the LGBTQ community clashed with police at Cooper’s Donuts and the Black Cat tavern in Los Angeles; at San Francisco’s Compton Cafeteria; and at Dewey’s restaurant in Philadelphia, among other skirmishes.

They organized rallies in Washington to protest the exclusion of homosexuals from military service, and met in Philadelphia each year on July 4 for “annual reminders” demanding legal protections.

Mattachine-New York helped end policies that allowed police ambushes. But police raids on bars and public toilets continued, and a series of violent homophobic attacks pushed the LGBTQ community to the brink.

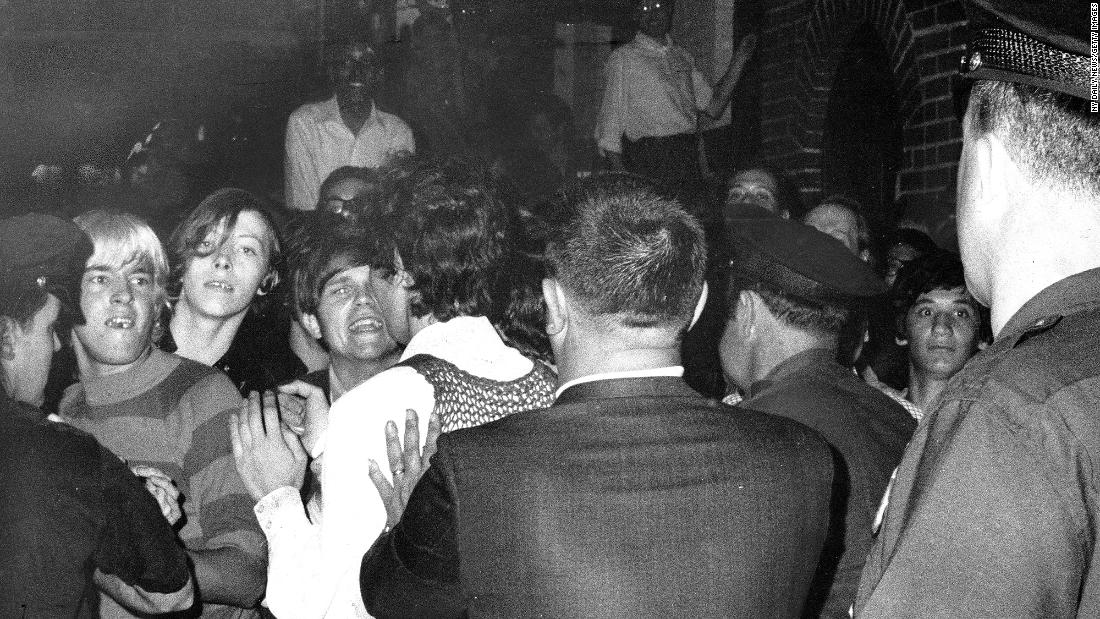

This was the scene outside the Stonewall Inn on July 2, 1969. (Larry Morris / The New York Times)

On Tuesday June 24th, the Police raided Stonewall, irritating customers who were tired of being harassed. But Deputy Inspector Seymour Pine, commander of the New York Police Department’s vice unit, did not back down.

He returned the following Friday with plans to vandalize the bar and slap the owners with enough infractions to shut down the bar once and for all. Almost immediately, police encountered resistance, Pine later told Carter.

Shortly after midnight, Bryan said he was walking down Christopher Street with a friend when a young man came running up.

“There’s a raid on Stonewall,” he announced.

He joined a crowd that was gathered across the street in a small plaza. As officers wrestled with a “tomboy lesbian” who was resisting arrest, Bryan said the crowd threw whatever they could get their hands on: coins, bricks, bottles.

Police chased protesters through the streets of Greenwich Village as Bryan watched as a “choir line” formed in front of officers and began to chant.

Carter and Marcus said photos from the first night show a “rainbow of children,” apparently street children and homeless LGBTQ youth, who were likely the main instigators.

What kept the riots alive?

News of the riots spread through the city the next morning. The first night it drew 500 to 600 people, but an estimated 2,000 people turned up outside the bar on Saturday night.

Members of the crowd held hands in bold displays of public affection. They chanted “gay power”, “we want freedom now” and “Christopher Street belongs to queens”.

To block Christopher Street, they formed a human chain and flipped over a car, attracting riot police who sparked more clashes.

In the midst of the tumult, a crowd invaded a taxi and the driver had a heart attack: he was the only person killed in six nights of protests.

The next three nights were relatively quiet, probably because people had work the next day.

On the third day of the riots, these messages were written on the windows of the Stonewall Inn. (Fred W. McDarrah/Getty Images)

By Wednesday, the protesters were back—inflamed by the media’s coverage of “gay cheerleaders” and “Sunday craziness.” News of the clashes had also spread to other leftist groups, who saw an opportunity to align themselves with the insurgent movement.

Overall, 21 people were arrested, most of them on the first night, and many police officers and protesters were injured. But there was a spark.

What happened after?

The energy of the uprising continued for weeks.

Weeks later, Mattachine-New York led a “gay power” march from Washington Square Park to Stonewall that drew hundreds of people.

Other Stonewall veterans favored more radical action. A new group including former Mattachines and feminists joined the Gay Liberation Front.

They did dances to raise money to show they didn’t need the Mafia to have fun. Proceeds financed an underground newspaper, a members’ bail fund, and lunches for the poor. They questioned mayoral candidates in forums about their views on homosexuality.

The group began to fall apart within months. But out of its ashes another group was formed, the Gay Activist Alliance, which would focus exclusively on gay and lesbian issues.

Meanwhile, activist Craig Rodwell and his friends came up with another way to harness the power of Stonewall. He proposed moving the annual Fourth of July memorial in Philadelphia to New York for the anniversary of the riots.

Gay rights advocates marched to commemorate the 1969 Stonewall riots in Greenwich Village in New York. (Leonard Fink/The Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender Community Center via AP)

On June 28, 1970, Rodwell and thousands of others returned to Greenwich Village for the first Christopher Street Liberation Day march. It became an annual event and evolved into the Pride parade, held each year in New York and other cities around the world.

“There were no floats, no music, no boys in their boxer shorts. The cops turned their backs on us to convey their disdain, but the masses of people continued to carry signs and banners, chanting and waving to the shocked onlookers,” said Fred Sargent, the fellow from Rodwell, on first gear.

“It was only after the march that these gay pioneers realized what could be possible.”