France was shaken to the core by the brutal killing of school teacher, Samuel Paty, and now shockwaves are resonating well beyond the country”s borders.

Paty was beheaded for doing his job; showing controversial caricatures of Islam’s most important Prophet, Muhammad, during a class on freedom of expression. Today, in the Netherlands, other teachers now fear for their lives for giving the same kind of lessons.

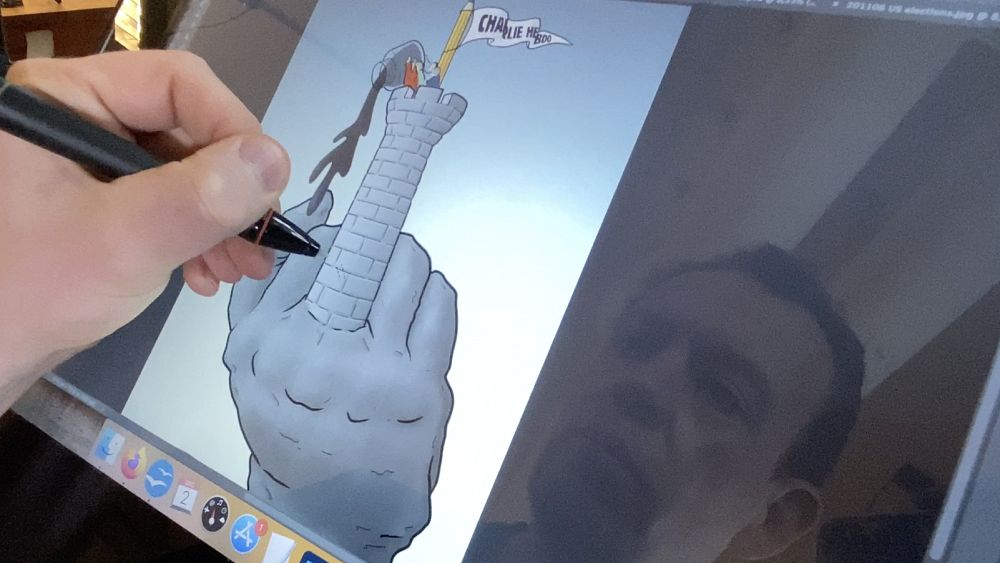

One of the teachers at Emmaus College in Rotterdam has been absent for weeks. He went into hiding after he received threats following the school’s commemoration for Samuel Paty. It was only after this commemoration that some students noticed a caricature in support of the French satirical newspaper, Charlie Hebdo, hanging in his classroom. Despite the fact that it had been there for five years. The photo of the cartoon was posted on social media with a threat. A young student was arrested.

Representatives from Emmaus College have refused to comment to us on this.

Rifts in Dutch society

The murder of the French school teacher has opened old wounds in the Netherlands and highlighted how divided the country is when it comes to freedom of expression and religion.

We talked to some students from Emmaus College to see how they felt about the events that led to the teacher’s murder. Opinions varied. Some believe the teacher was “just using his constitutional rights to express his opinion”. Others think it’s not appropriate to use cartoons in the classroom because children may have different beliefs. Some think showing something positive about religion is good, but “cartoons are most likely to be negative”.

In the full Unreported episode in the media player above, we’ve only shown parts of the cartoon that renewed debate in Dutch society. But the cartoon in its entirety shows a headless Charlie Hebdo cartoonist sticking out his tongue at a jihadist wielding a bloody sword. It’s entitled “Immortal”.

A number of Emmaus College students have wrongly interpreted the jihadist as the Prophet Muhammad.

Clamming up

We knocked on the doors of eight mosques and just as many schools, but nobody wanted to discuss cartoons and freedom of expression with us.

In the end, a teacher from another school did agree to talk. He said that he has never felt in danger, but asked to remain anonymous anyway. We discussed whether cartoons should be shown at school. This is what he thinks:

“Provocation needs to have a goal.

“If the intention is to shock and then have a conversation with your children about these things then maybe it’s suitable.

“But, you know, I also talk about sex in my classroom and we talk about porn movies, I’m not showing those movies.

“We can talk about it without showing the pictures.”

Two Dutch Imams have asked for the blasphemy law under which it is a crime to insult God, to be restored. It was scrapped in 2013. But others believe freedom of speech should be protected at all costs. One Member of Parliament from the leading Conservative party, Dilan Yeşilgöz-Zegerius, says “We will be tougher in our approach to people who threaten cartoonists, journalists, lawyers and judges.”

_Where do cartoonists stand on the subject? _

We asked Tjeerd Royaards, the editor-in-chief of a global cartoon movement in Amsterdam if there should be limitations to their work?

He said “Making satire and making editorial cartoons is all about operating on the fringes of freedom of expression and exploring where those boundaries are. The difficulty of this day and age is that violence comes into the equation when you’re talking about consequences for cartoons”. He doesn’t think creating new boundaries is going to help because “Cartoonists have self-censorship and have subjects that they will or won’t draw about. They have, visual references that they will or won’t use. Freedom of expression isn’t limitless.”

Charlie Hebdo is not where the polemic began. The Danish newspaper, Jyllands-Posten, was the first to publish cartoons deriding the Prophet Muhammad in 2005. The French satirical magazine republished them and added more of their own. In 2006, the former Executive Editor of Charlie Hebdo, Philippe Val said that their work is not a provocation, it’s “Exercising one’s right to freedom of caricatures and freedom of the press”.

But everyone knows what happened next. The assault on Charlie Hebdo in 2015 marked the start of a string of jihadist strikes that have taken around 400 lives in Europe and over 200 in France so far.

Samuel Paty was one of them and his murder wasn’t an isolated event. Weeks after his death in Nice, three people were killed in an Islamist terrorist attack inside a catholic church. Vienna was next. A shooting close to a major synagogue left four dead. The Islamic State took said they did it.

But going back to the Netherlands, how widespread is radical Islam there? Is it fertile ground for a terrorist attack? We asked this question to a Muslim organisation, SPIOR, that represents seventy mosques in Rotterdam. One of their jobs is to mediate between Islam and secular institutions. Its manager, Zakaria Chiadmi, said “I cannot assure one hundred percent that it will never happen here. We had our share of incidents in the Netherlands, not directly from the Muslim community, but by lone soldiers.”

A murder that is still on everyone’s mind in the country is that of one of its most controversial and famous figures, Theo Van Gogh.

He was killed 16 years ago. The film director and “enfant terrible” paid for his provocations of Islam with his life. Bicycles ride over the chalk outline where he was killed without even noticing it now.

The editorialist Ebru Umar worked with Van Gogh for years. She is an outspoken supporter of freedom of speech. She learned the hard way that it comes with a cost. She says “Everything we wrote was fun, but it was also challenging. But there was humour in what we wrote. We would never think a murder on religious Islamic grounds would take place. Then it happened.”

Van Gogh was a charismatic right-winger. He was shocking, just like his documentary on women and Islam. “Submission: Part 1”) with its explicit, provocative scenes are what sparked his murder by a Dutch-born Muslim. His colleague, Ebru, condemns the silence after these events. She believes that attacks will happen in the Netherlands and that society is just burying its head in the ground:

“We just want to ignore it as long as it doesn’t happen in front of your own door, as long as it doesn’t affect you, just shut up about it.”

Violent protests broke out across the Muslim world in 2005 and 2006 after the cartoons featuring the Prophet Muhammad were published. Hundreds of people were killed during this rioting.

The same scenes are still happening today. Muslim countries reacted in the same way to French President Emmanuel Macron’s crackdown on radical Islam. But Macron’s new approach began before and continued after Paty’s death. So, has nothing changed since the cartoons were first published fifteen years ago?

Tjeerd Royaards believes that the work of cartoonists has become more dangerous and unpredictable. More threats are being made, “it’s just become a more complex environment to make cartoons in”.

Many questions remain on the subject of freedom of expression and religion. Does the concept of blasphemy need to be reconsidered by the Muslim community? Or does the Western world, need to rethink its secular principles and adapt to a population that is growing increasingly diverse?